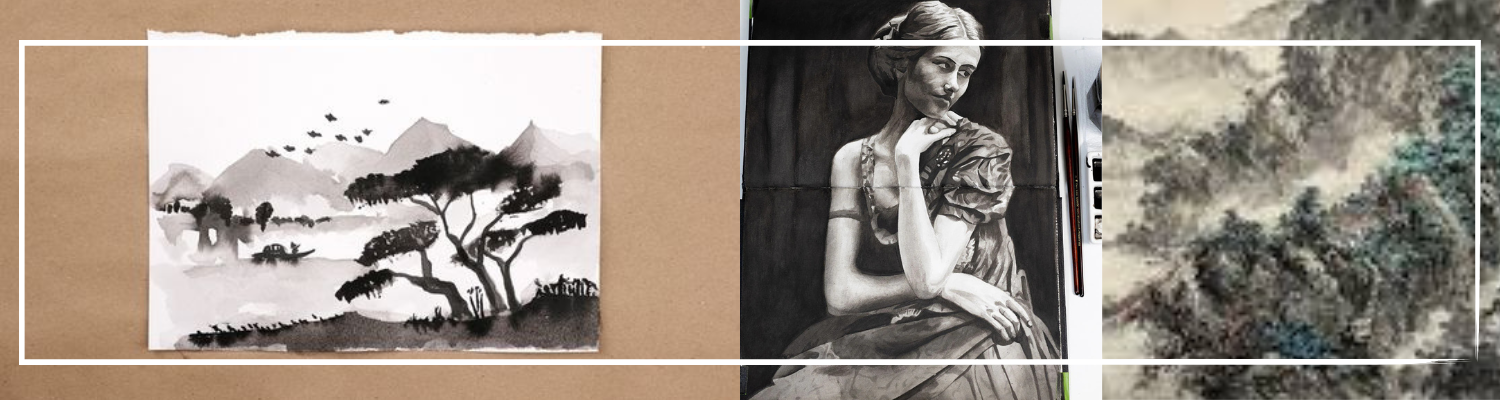

Ink wash painting, or Sumi-e, originates not merely as an art form but as a meditative discipline. Born from Chinese brushwork traditions during the Tang Dynasty, it filtered through Buddhist monasteries like water through rice paper—absorbed, reshaped, and transcended. The monochrome ink, soft yet deliberate, became a ritual in restraint, where brush met breath, and emptiness held form. Sumi-e is not about rendering; it is about revealing. Its origins are laced with philosophy, not just aesthetics. From rice scrolls to temple walls, from Zen gardens to Japanese paper screens, it shaped a visual language where silence speaks louder than color.

Sumi-e painting originated in China during the Tang Dynasty (7th–10th century), a period steeped in spiritual and artistic cross-pollination. Rooted in Daoist philosophy and later carried eastward by Zen Buddhist monks, its core was not ornamental but contemplative. The ink, derived from soot and glue, served as a medium of both spiritual expression and technical mastery. As it entered Japan during the 14th century, it became more than a transplant—it evolved into a Zen practice of mindful expression. Unlike the vibrant Chinese scrolls of courtly grandeur, Sumi-e focused on minimalism, capturing the essence with a single stroke. Mountains, bamboo, cranes, or chrysanthemums were less subjects and more metaphors, each brushstroke echoing the transient beauty of nature. Its origin lies not in just creating visual delight but in merging mind, paper, and ink into one unbroken gesture of awareness.

Ink wash painting’s journey across Asia was not linear—it flowed like ink itself, adapting and absorbing. In China, it began as a scholarly pursuit, a refined counterpart to calligraphy where brush control was everything. Korean artists later internalized it with Confucian sensibilities, crafting landscapes charged with symbolism and solitude. Japan, however, distilled it into Sumi-e, aligning it with Zen teachings. Here, minimalism met discipline—where one stroke could contain a mountain's presence or a monk’s silence. Vietnamese and Southeast Asian interpretations added floral exuberance and decorative flow, subtly diverging from Zen austerity. The medium shifted—from silk to rice paper, from scroll to screen—but the ethos remained: capturing essence, not likeness. As it evolved, the ink wash tradition became a collective breath across borders, shaped by each culture’s rhythm, religion, and respect for nature. Each line bore regional textures, but all pulsed with the same inked heartbeat.

Read More : Contemporary Paintings Guide: Artists, Buying Tips, and Care

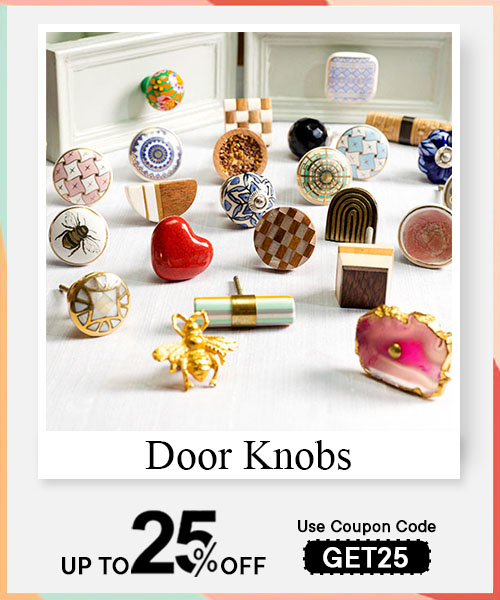

Sumi-e's transformation over the centuries was shaped by the triad of philosophy, patronage, and paper. As Zen Buddhism took firmer roots in Japan, it stripped the form of excess and centered the act of painting on the painter’s inner state. The brush became a mirror—each stroke a reflection of the artist’s presence, posture, and pause. Technological advances in ink production and the refinement of handmade paper allowed for subtler gradations and more fluid expressions. During the Edo period, secular themes entered the frame—landscapes gave way to portraits, flora, and narrative scrolls. Later, Western contact challenged traditionalists, but also provoked fusion: Sumi-e met modernism, abstraction, and even performance art. Yet, even amid these shifts, its spiritual rigor endured. The centuries did not dilute it—they distilled it. The transformation wasn’t a departure, but an unfolding. Sumi-e matured like aged ink: darker, denser, yet more transparent in its intent.

In the hushed breath of Sumi-e, brush meets paper not as a tool of control, but as a vessel of surrender. This artform is not merely a technique—it’s a conversation with impermanence. Core to Sumi-e is the ability to simplify without stripping meaning, to reduce without erasing spirit. Every stroke channels the unspoken: breath, stillness, emptiness. Here, less is not minimalism—it’s metaphysical. These principles are bound to intuition rather than instruction, to observation over ornamentation. Through disciplined spontaneity, Sumi-e becomes an act of mindful being, not just image-making—a spiritual residue of the present moment rendered in tones of silence.

Ink wash painting, or Sumi-e, orbits around the tenets of simplicity, spontaneity, and balance between form and void. It borrows deeply from Taoist and Zen philosophies, where nature is not conquered but mirrored. The guiding philosophy asks the artist to feel before depicting, to observe the rhythm of life without distorting it with ego. Each brushstroke is not only physical but spiritual—loaded with intent, clarity, and a deep sense of respect toward the subject. The aim isn't to replicate what is seen but to capture its essence. Emptiness is as vital as fullness, absence as powerful as presence.

Zen filters into Sumi-e not as a style but as an awareness. The artist approaches the canvas in a meditative state, where the mind is quiet and the body flows with controlled freedom. It teaches the value of ‘no-mind’—a state where thought dissolves, and only pure action remains. Sumi-e becomes an extension of this consciousness, not a pursuit of perfection but of presence. In Zen, the process is everything; thus, a painting might be complete in one breath. There is no overthinking, no revisions—only acceptance of the now. This surrender is what gives Sumi-e its intimate emotional resonance.

In Sumi-e, restraint and imperfection are not flaws; they are philosophies. A brush held too tightly stifles, and lines overly corrected become lifeless. Artistic strength lies in the gaps—the ‘ma’—the spaces between strokes, the breath between intentions. Imperfection reflects nature: asymmetrical, flawed, beautiful. Restraint ensures each gesture is meaningful, not cluttered. The artist must stop just before over-articulating, allowing the viewer to complete the image. This dynamic silence becomes a participatory space. It’s in the deliberate restraint and quiet imperfection that Sumi-e speaks most honestly, revealing emotional truths that polished precision often mutes.

Tools in Sumi-e are not passive objects; they are memory keepers, spiritual extensions of the hand. The “Four Treasures”—brush, ink, paper, and inkstone—are revered not for their utility alone, but for their heritage, feel, and interaction with the artist’s spirit. Each responds to touch differently, each reacts to pressure like a breath to skin. Ink bleeds into paper not just visually, but viscerally. A handmade brush curves to the soul’s rhythm. Tools are chosen not for luxury but for honesty—for the way they honor water, absorb hesitation, and translate gesture into emotion. Their humility amplifies Sumi-e’s transcendence.

Sumi-e rests on four sacred elements: the brush (fude), ink stick (sumi), inkstone (suzuri), and paper (washi). The brush—typically made from animal hair—must be supple yet strong, capable of thick and thin lines in one breath. The ink, made from soot and glue, is ground on the inkstone with water—a ritual in itself—connecting the artist to time. Rice paper or mulberry-based paper absorbs ink uniquely, allowing for fluid bleeding, gradation, and control. These materials don’t just support expression—they shape it. Their organic fragility demands respect, enhancing the contemplative nature of the practice. Each tool teaches patience, control, and surrender.

Ink, paper, and brush aren’t neutral mediums; they define the painting’s character. Ink’s density and fluidity determine emotional weight—thicker ink lends gravity, while lighter washes evoke ephemerality. Rice paper absorbs unpredictably, bleeding lines into ghostly edges that suggest rather than declare. Brush type matters: a soft brush flows like breath, a stiff one resists like stone. Goat hair brushes create elegant washes; wolf hair brings precision. The combination is like composing music—each element carries tone, rhythm, silence. Change one, and the harmony shifts. The outcome is less about control and more about collaboration—with tool, touch, and timing.

Handmade tools possess memory. The fibers, grains, and natural imperfections retain energy from every use. A hand-forged brush responds with nuance—bending, springing, breathing with the artist’s rhythm. In contrast, synthetic tools often resist, delivering uniformity but sacrificing depth and soul. Handmade ink, ground with care, yields richer tonalities; its tactile ritual roots the painter in the moment. Handmade paper weaves in unpredictability—fibers catch ink like skin holding warmth. These tools whisper back. They remember. In Sumi-e, where emotion and motion blur, the organic essence of handmade tools lends a living, breathing texture to the work—one no synthetic can mimic.

Ink wash painting, or sumi-e, lives between breath and brush, silence and expression. Every stroke becomes a philosophy—a distilled thought born in the moment. Techniques are not merely methods; they’re rituals that evoke spirit through gesture. The paper is never merely a surface, but a field of movement where ink translates mood, void, and rhythm. Precision merges with spontaneity—an elegant paradox. From feathered wisps to deep saturations, each effect arises not from complexity but restraint. Brushwork, ink dilution, water discipline—these are not tools; they’re vocabularies. Technique in sumi-e is both form and freedom—simplicity wielded with surgical emotion.

Foundational brushstrokes in sumi-e are elemental movements—vertical, horizontal, dot, hook, sweep—each one designed to embody a principle of nature. These strokes are not decorative, but declarative: they hold gesture, intent, and tone. The “Bone Stroke” is foundational—used to render form and skeletal structure in bamboo, birds, or mountains. The “Flying White” technique, where the brush skips and lifts, exposes the fibers of the paper, imitating wind or age. Wrist control, breath pacing, and point-of-contact determine the liveliness of a stroke. Ink weight—dense, diluted, or dry—further defines each line’s emotion. Training often begins with copying masterworks, not as mimicry, but as a ritual of entering the brush’s memory. The goal is not accuracy but spirit transfer. These brushstrokes are meditative actions that train the hand to listen as much as it speaks, inviting a space where the artist’s internal landscape pours gently onto the paper.

Shading in sumi-e is not a gradient of graphite but a dance between water and will. Artists use varying dilutions of ink—from rich, undiluted black (nÅtan) to barely-there greys—to build dimension and atmosphere. The key lies in water control: more water means lighter tones; less, darker and more assertive. Artists use multiple brushes or rinse between passes to create seamless tonal transitions. Layering plays a role, but unlike Western shading, it’s not about realism; it’s about rhythm. A mountain is not shaded for light logic but to suggest weight or silence. Water must be tamed and anticipated. Sometimes, a single stroke holds five shades, where the brush is charged with full ink at the tip, lighter grey at the belly, and almost clear at the heel. It’s choreography on paper. Ink and water are not passive materials—they are co-performers in the painting’s breath.

Dry brush and wet ink methods in sumi-e are contrasts of intensity—each technique a unique philosophy. The dry brush (kasure) uses less ink and minimal water, producing broken, textured lines that reveal the tooth of the paper. It suggests age, bark, erosion, or emotional brittleness. It’s where silence creeps into the painting. Wet ink (nÅyÅ) saturates the brush, allowing fluid, continuous strokes. It represents fullness—of foliage, clouds, or emotion. Wet techniques flow, while dry ones whisper. The control is not just in moisture, but in pressure, angle, and pacing. Artists often juxtapose the two: a gnarled pine with dry twigs and wet leaves; a rock outlined in dry ink with shadows washed in wet gradients. Dry techniques expose process; wet ones conceal it. One fractures the gesture, the other extends it. The balance between the two is not visual alone—it’s a spiritual calibration of presence and absence.

Sumi-e—like a whispered thought on silk—uses brush, ink, and water not only to depict the world, but to distill its essence. Every element breathes symbolism. It is not merely image-making but image-becoming. The artist does not impose form; he releases it from emptiness. Each stroke is deliberate, guided by restraint and emotional intention. The brush flutters like breath, carrying stories, philosophies, and spiritual clarity. Nature is not a subject—it’s a mirror. Whether bamboo, koi, or blossom, these are not “decorative motifs.” They are poetic metaphors living in the stillness of the paper. Here, form follows feeling, and feeling follows void.

Bamboo, in Sumi-e, stands tall yet bends—signifying resilience, humility, and the flexibility of the noble spirit. Each stalk is a moral backbone, upright yet yielding to wind. Plum blossoms bloom against the bitter frost—an allegory for beauty in adversity and the renewal of hope. Their fragile petals balance endurance and grace, a paradox often evoked through light brush lifts. Koi fish, often inked in gentle curves, are the archetypes of perseverance and destiny, swimming upstream against currents. Their portrayal is motion within stillness—ripples caught in time. Each subject is more than symbol—they’re emotional archetypes, carrying philosophical weight. The placement, angle, and shading of each determines whether it whispers a story of patience, transformation, or quiet strength. Together, these motifs are not decorative—they are strokes of moral and spiritual clarity, inscribed into silence.

In Sumi-e, mood is not created—it is summoned from the breath between strokes. Minimalism doesn’t mean absence; it means precision, a meditation on what is essential. The economy of line becomes the luxury of emotion. One flick of a brush can suggest melancholy, tension, or freedom. A sparse landscape with just one slanted pine and distant mist can evoke loneliness deeper than a thousand words. Composition here is not balance—it’s asymmetry with intent. The use of vertical space might suggest longing; a descending line could whisper descent or surrender. Often, mood comes from what’s implied, not rendered. Like haiku, it lets ambiguity do the emotional heavy lifting. A bird mid-flight, only half rendered, becomes a longing, a wish, a memory. Minimalism, in this form, is not lack—it is emotive clarity, sculpted from silence.

Negative space in Sumi-e is not background—it is breath, pause, potential. It is the realm of the unseen, the implied, the meditative. Unlike Western art, which fills, Sumi-e empties. This void is not emptiness—it is charged with intention. It suggests the air between mountains, the distance between words, the time before a thought arises. The eye does not merely rest here; it contemplates. The placement of one tree in a sea of white can evoke isolation, introspection, even the vastness of time. This space allows the viewer to complete the painting with their own emotion and perception. It is the unsaid in a poem, the breath between musical notes. Without negative space, Sumi-e would lose its echo, its stillness, its spiritual tension. The blankness is not silence—it is resonance.

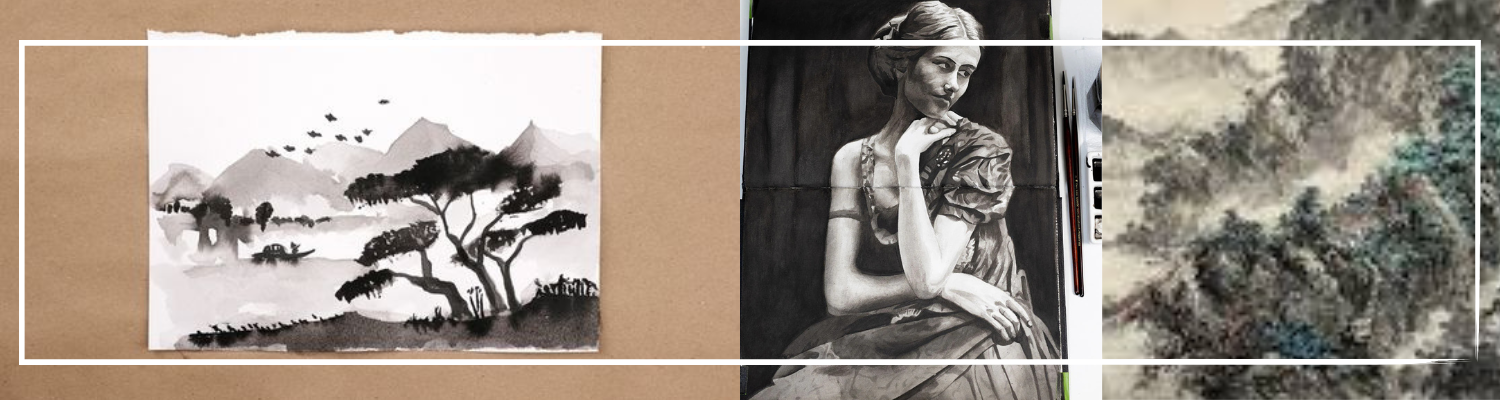

In the current artistic landscape, Sumi-e and ink wash painting are not merely carried forward—they are reinterpreted, re-contextualized, and reimagined. Contemporary artists draw from its silent meditativeness and minimalist aesthetic to explore deeper emotional terrains. From gallery canvases to NFT art, Sumi-e’s brushstrokes are being bent into new media without diluting its philosophical core. Some artists preserve the ink-on-rice-paper purity; others blend it with photography, calligraphy, or abstract expressionism. The techniques remain faithful to balance, void, and rhythm—yet the themes speak of urban solitude, diaspora, ecological anxiety, or even digital disconnection. It’s tradition dissolving into modernity without losing its soul.

Modern artists are adapting Sumi-e not as imitators of tradition but as interpreters of emotion. They often begin with the classical four treasures—ink stick, brush, paper, and stone—but transition into experimental formats. Some retain the monochrome elegance but use mixed media like charcoal, graphite, or textured acrylics on unconventional surfaces such as wood, concrete, or translucent film. Others translate the same brushstroke philosophies into kinetic movement in animation, performance art, or contemporary dance, treating the body like a sumi brush in space. The core remains: spontaneity, spiritual immediacy, and compositional asymmetry. Yet, today’s themes often focus on climate grief, diaspora, digital loneliness, or socio-political unrest. Thus, the whispering poise of Sumi-e speaks modern dialects without ever shouting.

Digital artists have developed nuanced tools to simulate the ink bleed, grain, and gestural flair of Sumi-e. Software like Adobe Fresco, Procreate, and Corel Painter offer Japanese brush sets that replicate the drag, pressure sensitivity, and water-to-ink ratios. Custom brushes mimic the porous absorption of washi paper, while AI-based stylus pressure emulates the fluidity of hand-brushed lines. Texture overlays replicate feathering, backwash, and wash gradations. Even 3D tools like Blender now incorporate NPR (non-photorealistic rendering) shaders that allow for animated ink brush effects. The true craft lies not in copying brushstrokes but understanding the philosophy of intentional imperfection and asymmetrical elegance. In skilled hands, the digital sumi-e becomes not a reproduction—but a reinterpretation of impermanence and flow.

In the global art diaspora, Sumi-e is transcending its East Asian roots to become a transnational, transcultural language. Artists in Europe and the Americas blend it with Western calligraphy, Arabic geometric patterns, or Indigenous symbolic structures. It’s used in graphic novels, tattoo art, set design, and even street murals. Collaborative works often pair the negative space aesthetic of Sumi-e with vibrant color palettes or narrative elements from folklore traditions across the globe. A Brazilian artist might pair it with Amazonian flora; a Black American painter might infuse it with Afrofuturist themes. These hybrid pieces still follow Sumi-e’s principle of “less is more”—but they speak with accents. In this fusion, Sumi-e becomes a vessel for shared humanity, not just inherited aesthetics.

The discipline of Sumi-e—or ink wash painting—is not just about the act of painting, but also about the meditative respect for the tools themselves. Brushes, ink stones, and paper are not disposable implements; they are revered extensions of the artist’s spirit. Each carries memory, intention, and energy. Maintaining them is a mindful practice—a ritual that aligns with the essence of wabi-sabi: appreciating impermanence while preserving grace. The balance between gentle care and practical upkeep adds longevity to your tools while preserving their artistic soul. When cleaned and handled with care, they retain the subtlety and fluidity that make Sumi-e so evocative. Below are answers that delve into specifics.

Brushes should be rinsed gently in lukewarm water immediately after use. Avoid soap or harsh detergents, as they degrade the animal hair and affect ink absorption. Rotate the brush slowly between your fingers while rinsing, allowing residual ink to bleed out naturally. Then reshape the bristles into a fine point and hang the brush bristle-side down to dry, preventing water from seeping into the bamboo handle and causing cracks.

Ink stones should be wiped with a soft, damp cloth. Never scrub or use abrasives, as the delicate grinding surface must remain even and porous. After every session, remove excess ink with a wet brush, gently wiping in the direction of the grinding. Dry it thoroughly to avoid mold or staining. This ritual of cleaning is as meditative as the painting itself—imbued with calm and precision.

Preservation begins with proper storage and thoughtful usage. Always keep brushes in a cool, dry environment—preferably hung vertically or laid flat in a brush roll, avoiding pressure that could distort bristles. Don’t cap or trap damp brushes; this breeds mildew. Avoid resting them in water jars—waterlogged ferrules cause swelling and breakage over time.

Ink sticks must be kept dry and wrapped in silk or stored in a box to shield them from humidity. Ink stones should be stored flat with a protective cloth to prevent micro-abrasions. Paper should be stored away from sunlight and moisture—ideally in archival sleeves. Limit physical contact, especially with oily fingers. The underlying principle here is restraint—treating every tool as if it holds the memory of your last gesture. That reverence translates directly into longevity and beauty.

Maintenance isn’t just occasional—it’s woven into the rhythm of your painting practice. Brushes demand daily cleaning post-use, but a more thorough inspection every few weeks ensures bristle integrity, checks for stray hairs, and evaluates moisture damage. Once a month, condition your brushes with a light application of natural hair conditioner diluted in water, then rinse thoroughly.

Ink stones need wiping down after each use, but once every few months, give them a soft-brush dry cleaning to remove residue buildup. Ink sticks can last years but should be checked periodically for cracks or mold, especially in humid climates. Seasonal shifts are a good prompt for deep tool maintenance. This cadence of care keeps your process ritualistic and grounded—a cyclical act of renewal that parallels the nature-bound essence of Sumi-e. It ensures the tools become an extension of your evolving artistic hand.

Read More : A Comprehensive Guide to Rococo Painting: Style, Artists, and Influence

Sumi-e paintings, or ink wash works, embody ephemeral strokes and deliberate silence. Their preservation isn't just technical—it's devotional. The fragility of rice paper, the breath of black ink, and the handmade textures demand an environment that honours their soul. Framing becomes a ritual, not a task—each material used should reflect a harmony with the painting's breath. Whether stored in silence or displayed under controlled reverence, the preservation of Sumi-e is less about confinement and more about allowing it to live untouched by time. Museums treat them as meditative relics, balancing science and sanctity in equal measure.

Long-term preservation of Sumi-e—or ink wash paintings—relies on maintaining stable humidity (ideally 50%) and temperature (around 18–21°C) to prevent mold, paper warping, and ink fading. Direct sunlight must be strictly avoided; ultraviolet rays not only bleach pigment but disrupt the spiritual stillness of the work. Airborne pollutants, including sulfur dioxide and dust, should be filtered through archival enclosures or display cases. Acid-free backings, pH-neutral mat boards, and UV-protective glass provide a layered defense against environmental degradation. Light levels should remain below 50 lux for exhibited works. Silence, in this context, isn't metaphorical—it’s physical: minimal handling, vibration, and movement are crucial. Preservation is about maintaining the painting's breath—its airy texture, subtle tone gradients, and atmospheric balance. In essence, ideal conditions are not just about safety—they’re about aligning with the artwork’s natural rhythm, allowing each brushstroke to remain alive without disruption from the passing world.

Sumi-e paintings should be stored flat or gently rolled with acid-free tissue between layers to prevent smudging or ink transfer. Avoid tight rolling—ink can crack over time. When framing, always opt for archival matting and non-invasive mounting techniques. The ink wash’s porous texture demands breathing space—use deep-set frames to create distance between the glass and artwork. UV-filtering museum glass or acrylic should shield it from harmful light. Avoid adhesive tapes or glues directly on the artwork; instead, use Japanese-style paper hinges attached with reversible wheat starch paste. Frames must remain sealed to block pollutants and insects. Always install a backing board to buffer changes in humidity. If stored, horizontal drawers with individual slots and a climate-controlled room are optimal. The philosophy is simple—frame not to showcase but to shield, to offer sanctuary. The goal is preservation through reverence, treating each artwork like a poem pressed into fragile skin.

Museums treat Sumi-e as cultural whispers—aesthetic relics that require minimalist but exacting care. Conservation starts with detailed condition reports, noting ink density, paper age, and past restorations. Humidity-controlled vitrines and rotating display schedules limit overexposure. Traditional Japanese techniques—such as urauchi (lining with handmade paper) and sousou (mounting on scrolls)—are employed using natural adhesives like funori (seaweed glue) or wheat paste. Digital imaging and infrared scans track ink layer integrity over decades. When tears occur, kintsugi-like principles are adapted—not to erase flaws but to honour aging gracefully. Insects are deterred using natural repellents like camphor rather than chemicals. Conservators wear gloves, use soft brushes, and even replicate the traditional mounting room's architecture during treatment. It’s not just technical—it’s philosophical. Conservation here respects the spiritual cadence of brush and void, preserving not only the medium but the silence between each stroke. The artwork is never owned—only temporarily protected.

The lineage of Sumi-e—also known as ink wash painting—is a river of meditative rigor, poetic essence, and silent mastery. Rooted in Zen philosophy, its masters didn't merely paint; they invoked presence. From classical pioneers like SesshÅ« TÅyÅ to the contemporary elegance of modern ink minimalists, each stroke becomes a testament to discipline and depth. The tradition is defined not only by technical finesse but by how silence is rendered visible. Artists serve as both monks and craftsmen, their brushwork dissolving the boundaries between form and void, intention and spontaneity—cultivating a tradition where emotion and nature are indivisible.

The classical Sumi-e tradition reveres figures like SesshÅ« TÅyÅ, Muqi Fachang, and ShÅ«bun—each a monk-artist whose aesthetic revolved around Zen's inward gaze. SesshÅ«’s precision of line and mist-veiled landscapes redefined monochrome depth; his use of haboku (splashed ink) reflected spontaneity governed by meditative clarity. Muqi's pieces like the Six Persimmons are paragons of symbolic abstraction—each fruit suspended in empty space, yet loaded with moral metaphor. ShÅ«bun, a bridge between Chinese Song influences and Japanese sensibilities, brought contemplative restraint into formalized pictorial structure. These artists weren’t just painters—they were visual philosophers, mapping mountains and spiritual terrain with the same brush, creating a tradition that still whispers in every sumi stroke.

Modern Sumi-e artists fuse ancient spontaneity with contemporary design awareness. Figures like Yasuo Kuniyoshi, TÅkÅ Shinoda, and Chiura Obata integrated Western abstraction, feminist undercurrents, and American landscapes into the Sumi-e philosophy. Shinoda, especially, blurred calligraphy and modern minimalism—her brushed compositions often punctuated with emptiness, tonal harmony, and gestures that felt like whispers caught mid-breath. Obata, meanwhile, brought Japanese ink realism into the Sierra Nevada’s topography, blending East with the American West. In their hands, ink moved beyond tradition—it evolved into a dialogue between stillness and movement, memory and immediacy. These signatures are less about mimicking form, more about translating essence—turning gesture into emotional architecture.

SesshÅ« TÅyÅ didn’t just influence Sumi-e—he transfigured it. A Rinzai Zen monk trained in both Japanese and Chinese traditions, his work merged the literati ethos of the Song Dynasty with uniquely Japanese abstraction. His use of haboku (broken ink) introduced a kinetic looseness that mirrored the spontaneity of nature and mind. SesshÅ«’s compositions weren’t “drawn”; they were breathed—mountains rising through mist, trees stretching in wind-like script. Later artists like Hasegawa TÅhaku furthered this emotive landscape style, using negative space as philosophical terrain. Collectively, they expanded Sumi-e from a mere pictorial practice into a spiritual and psychological ritual—each brushstroke a confrontation with the self.

Sumi-e painting, at its core, is not merely a technique—it is a discipline, a meditation, a rhythm rendered in monochrome. To learn Sumi-e is to embrace patience and silence, to let breath guide the brush and allow white space to speak. The early stage of practice isn’t just repetition; it is a spiritual alignment between mind and material. Ink becomes breath, paper becomes pause. Mastery begins not with complexity but with control—the weight of the brush, the saturation of the ink, the intention behind every movement. It is a dialogue of restraint, where each line is both a statement and a surrender.

Beginners should begin with the philosophy before the technique. Sumi-e isn’t just about aesthetics; it is about becoming present. Start by gathering traditional tools: a bamboo brush (fude), sumi ink, ink stone (suzuri), and rice paper (washi). Then, focus on breathing. Your breath must guide your strokes—short, long, heavy, light. Begin with enso (the Zen circle) to feel continuity and flow. Copying basic strokes from master works is essential, but do not rush. Sumi-e rewards patience and precision, not speed. Each line should carry intention. Also, learn to mix and grind your own ink—it humbles and centers the mind. Avoid overloading the brush or working on thick paper. Remember, you're not just creating forms, you're communicating spirit—"bokuseki" (traces of the brush) should feel alive, not mechanical. Above all, return to simplicity—a single bamboo stalk can be your whole lesson for a week.

Mastery in Sumi-e begins with mastering the brush. First, practice lines and dots—long vertical strokes, horizontal sweeps, then dots with varying pressure. This enhances your wrist flow and control. Next, explore gradation exercises—load your brush with ink and execute strokes that fade as the ink thins out. This introduces you to “bokashi”—the technique of tonal blending, an essence of mood in Sumi-e. Then move to the Four Gentlemen: bamboo, orchid, chrysanthemum, and plum blossom. Each offers compositional training in different directions—vertical (bamboo), curved (orchid), clustered (chrysanthemum), and branched (plum). Use negative space as an anchor, not a void. The placement of emptiness is as intentional as the brushwork. Compositionally, work on asymmetry and balance. Paint on unruled rice paper and practice off-center subjects to enhance natural rhythm. Your hand will shake, the ink may bleed—that’s part of the language. Accept imperfection; let it speak.

Read More : Tempera Painting Technique: History, Definition, Process & Application Guide

Authentic Sumi-e training is best rooted in traditional lineage and mindful observation. Seek out Japanese cultural centers, Zen monasteries, or Asian art institutes with reputable instructors. Cities like Kyoto, Tokyo, and even international hubs like San Francisco, Paris, or Delhi host masters who teach not only form but the philosophy embedded within each stroke. Online, explore schools such as the International Sumi-e Association, or masters like Shozo Sato and Kazu Shimura, who share comprehensive techniques. Watch master demos—not for copying—but for absorbing flow, Ma —the space between. Read foundational texts like The Spirit of the Brush by Saito or Zen Seeing, Zen Drawing. Yet, don’t rely solely on digital tools; Sumi-e is tactile. Attend retreats or workshops where silence is part of the curriculum. Training should not only elevate your brushwork but deepen your inner stillness. In Sumi-e, your growth is not on paper—it is in your pulse.