Sand paintings belong to memory itself, ancient hands shaping earth into visions. In Navajo culture, sand was never mere dust, it became prayer, path, and healing canvas. In Tibetan Buddhism, mandalas rose from colored grains, only to be dissolved, teaching impermanence. Across indigenous rituals, sand carried more than color, it carried breath, silence, and presence. Each grain became a note in a wider chant, each form a passage between human and divine. These paintings were not preserved, they were lived, spoken, and released, art as ceremony, history as a fleeting design upon the ground.

The earliest origins of sand paintings trace back to indigenous practices where earth itself became sacred language. Among the Navajo, sand served as a medium to invoke spiritual presence during ceremonies, believed to connect humans to holy beings. In Tibet, Buddhist monks developed mandalas of sand to embody impermanence, dissolving them once completed. Both traditions reveal sand as chosen for its transience, it resists permanence, demanding the viewer to confront time and mortality. The act of creating and erasing was as vital as the image itself, embedding philosophy, ritual, and community memory into fragile grains scattered on the earth.

Navajo sand paintings deeply influenced cultural traditions by serving as ritual medicine, storytelling, and cosmological maps. They were not decorative but functional, crafted during ceremonies like the Night Chant. The images summoned holy people, animals, and symbols believed to restore balance, harmony, and health. This artistic form reinforced communal memory, teaching younger generations mythologies and sacred narratives. Over time, the practice shaped how Navajo identity viewed illness, not as isolation, but imbalance requiring spiritual realignment. The paintings anchored Navajo thought, the earth as healer, color as voice, and ritual as bridge between unseen worlds and living communities.

Read More : How to Do Stencil Painting: Tools, Surfaces, and DIY Ideas

Tibetan Buddhist mandalas are created with sand to embody impermanence and sacred geometry as spiritual practice. Monks spend days or weeks placing colored grains with precision, forming a cosmic diagram of the universe. The process is meditation, each gesture carrying mantra and intent. Yet once complete, the mandala is deliberately destroyed, the sand released into flowing water. This act teaches impermanence, beauty must dissolve, attachment must fall away. For practitioners, the mandala is not just image but journey, a reminder that even perfection exists only for a moment, after which harmony lies in letting go, not in preservation.

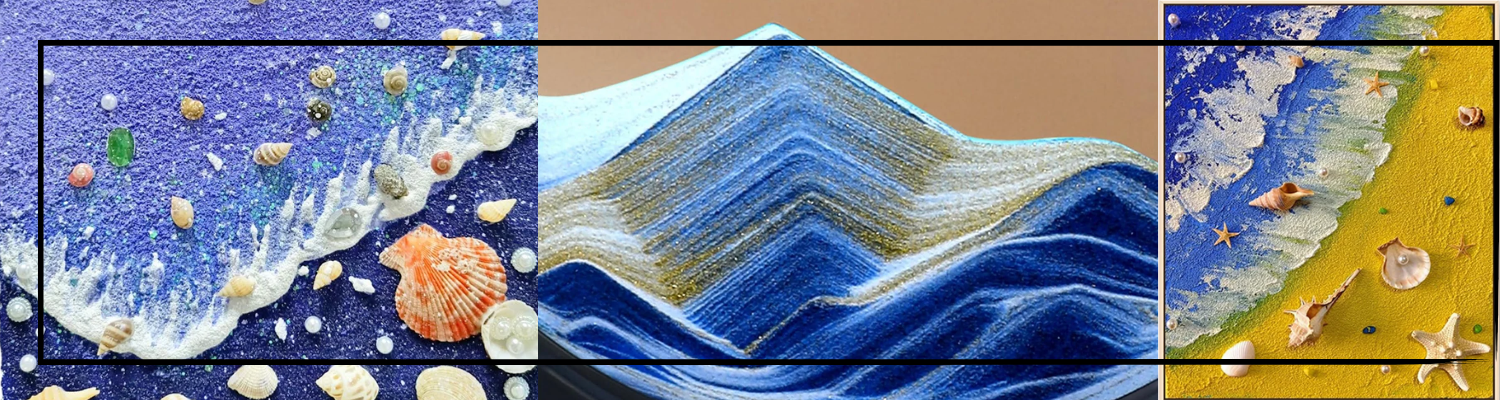

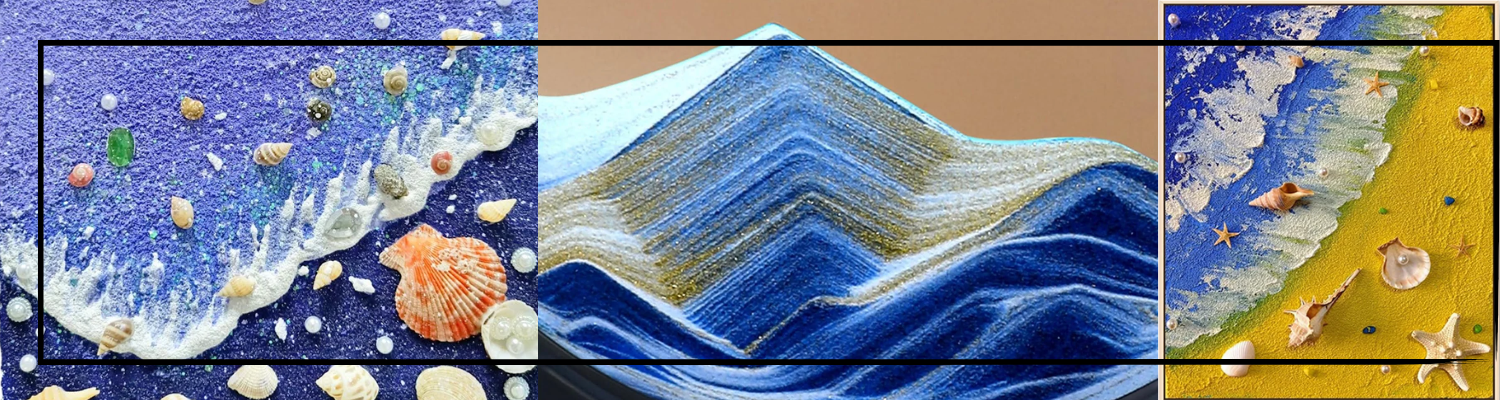

Materials in sand paintings carry both earth and vision. Natural pigments, crushed stone, and mineral powders provide tones that mirror land and sky. Artists sift and grind sand into colored shades, breathing into them ritual power. Preparation is slow, deliberate, as though each hue must be purified before forming symbol. From hand to earth, artists trace patterns that vanish with the wind yet endure in memory. Whether Navajo or Tibetan, the techniques share restraint and discipline. Each grain is placed with intent, each curve mirrors an inner map, art born not from permanence, but from reverence and release.

Traditionally, sand paintings relied on natural elements shaped into color and texture. Navajo artists used ground sandstone, pollen, charcoal, and crushed minerals to create rich hues reflecting desert landscapes. Tibetan monks employed fine sand dyed with mineral pigments, sometimes mixed with stone or flower dust, to achieve brilliance. These materials were never arbitrary, they embodied land, season, and sacred association. Yellow might signal corn pollen, red the earth, white the dawn. Using what the earth offered, artists ensured the art remained inseparable from nature itself. The materials transformed ground into cosmos, turning humble sand into sacred geometry and spiritual map.

Artists prepare colored sand with patience, transforming raw minerals and natural substances into fine, vibrant powders. The Navajo ground sandstone, clay, or charcoal, mixing them with pollen or plant materials to deepen hue. Tibetan monks dyed sand by crushing minerals like malachite for green, cinnabar for red, or lapis for blue, blending until texture was even and luminous. This preparation was not mechanical, it was ritual, a mindful act that honored material as sacred. By purifying and sifting each grain, artists ensured precision during creation. The sand was not just pigment, it was consecrated matter, charged with spiritual presence.

The creation of sand mandalas involves techniques of immense discipline and precision. Monks use metal funnels, called chak pur, to release controlled streams of sand, guiding grains into intricate lines and curves. The process begins with drawing a geometric framework, often based on sacred proportions, then layering colors with patience. The technique is collective, several monks work simultaneously, chanting as they align grains into cosmic patterns. Silence and rhythm guide the act, turning it into meditation rather than craft. Completion is never the goal alone, the gradual dissolution of the work is integral, transforming technique into spiritual teaching of impermanence.

Sand paintings live as symbols, not objects. Each line carries story, each curve invokes unseen beings. In Navajo tradition, the paintings summon deities to restore balance, embedding prayers in color and form. Tibetan mandalas mirror the universe itself, offering vision of cosmos within grains. Sacred geometry shapes the language of order, while ritual use turns symbol into act. Healing, meditation, remembrance, all find place in these fragile patterns. The religious significance lies not in permanence but in presence, in the way symbols breathe for a time, then return to earth, leaving only resonance within the human spirit.

Symbolic meanings in sand paintings reflect cosmology, healing, and spiritual connection. For the Navajo, figures of holy people, animals, and cosmic patterns represent harmony and restoration. Colors carry layered meaning, white as dawn, black as night, red as sunset, yellow as midday sun. Tibetan sand mandalas symbolize the universe itself, sacred palaces, deities, and protective guardians arranged in geometric order. Together, these meanings extend beyond decoration, they embody balance, impermanence, and cycles of existence. The symbolism transforms grains of sand into cosmic language, reminding communities that healing, order, and transcendence emerge not from permanence, but from fleeting, sacred design.

Sand paintings serve as healing portals, particularly in Navajo traditions. During ceremonies like the Night Chant, paintings are created on the ground where patients sit at the center. The symbols, deities, holy people, cosmic animals, are believed to summon divine power into the space, channeling harmony into the patient’s body and spirit. Healing here is not medical but spiritual, restoring balance between individual, community, and cosmos. The painting is temporary, once the ceremony ends, it is erased, symbolizing the illness itself has been carried away. Through this act, healing becomes not only physical restoration but reconciliation with sacred order.

Sacred geometry in sand mandalas is vital because it represents cosmic structure and spiritual order. The intricate patterns, circles, squares, lotus forms, are not abstract but symbolic maps of the universe. Each proportion is carefully aligned to reflect harmony, guiding meditation toward deeper awareness. For Tibetan monks, geometry functions as a spiritual language, the center symbolizes divine essence, while surrounding layers reflect protective forces, elements, and consciousness. This geometry is both visual and experiential, leading participants into contemplation. Its importance lies in its precision, reminding practitioners that the universe is interconnected, ordered, and transient, all within grains of colored sand.

Sand painting is not bound by one soil or one ritual; it breathes across regions with distinct tones of memory. Navajo sand paintings emerge as sacred, woven with prayers, where each color belongs to the earth’s own vocabulary. Tibetan mandalas rise like fragile universes, only to be dissolved, reminding us of impermanence. Indian Rangoli brightens thresholds, layered with auspicious patterns that speak of welcome, joy, and protection. Aboriginal art, grounded in Dreamtime stories, ties earth, spirit, and community together. Each variation is not merely visual, it is an act of living culture, carried by hand, intention, and rhythm of place.

Navajo sand paintings are not decorative gestures; they are ceremonies in dust. Every design belongs to healing, created inside rituals called “chantways.” Colors white, yellow, blue, black are drawn from natural earth pigments, each one symbolizing an element of the cosmos. Figures of deities, animals, and sacred patterns appear only under the guidance of a medicine man, because they are considered living prayers. What makes them unique is their impermanence; after the ceremony, they are swept away, as if to release the prayer back into the wind. The painting is never owned, never kept, but serves as a bridge between the sick and the divine. In this surrender, they embody a vision where art and spirituality are inseparable, and healing is not permanence but a moment of alignment between human life and the larger order of the universe.

Tibetan mandalas are intricate, geometric realms, cosmic maps built grain by grain. Unlike Navajo paintings, which focus on healing the individual, mandalas embody universal balance and spiritual training. Monks spend days, sometimes weeks, creating symmetrical patterns with colored sand funnels called chak pur, following strict iconography. These designs represent divine palaces and deities, functioning as meditation tools for both the creators and observers. While Navajo sand paintings are created within private rituals for specific needs, Tibetan mandalas are often public, inviting viewers into shared contemplation. And like the Navajo works, mandalas are swept away, dissolved into flowing water, to teach impermanence. Yet their difference lies in purpose, one cures, the other awakens. One restores a person’s body and spirit, the other reveals the cosmos as a fleeting, interconnected whole. The contrast is not opposition but complement, healing of the part and vision of the infinite.

Rangoli is a threshold art, drawn each dawn to invite auspiciousness into the home. Its designs vary across India, geometric in Tamil Nadu’s kolam, floral in Maharashtra, peacock motifs in Gujarat, but all echo the idea of welcoming prosperity. Unlike Navajo or Tibetan works, Rangoli is not tied to ritual destruction but daily renewal, erased by footsteps, wind, or rain, and reborn again the next morning. They are made with rice flour, flower petals, or colored powders, ensuring that birds and insects can feed on them, merging beauty with nourishment. Each Rangoli reflects cultural rhythms, festivals, harvests, marriages, turning private homes into open sanctuaries. Beyond design, it is a practice of devotion, of women rising before sunrise, bending low to the earth, their palms tracing patterns of continuity. It is not just art but a lived dialogue between household, cosmos, and community.

Sand has shifted from ritual soil to stage spotlight. Contemporary sand art embraces performance, turning fragile grains into moving narratives. Artists draw and erase images on backlit glass, projected on screens as live storytelling. Sand animation bends tradition into cinema, layering memory and imagination with each swipe of the hand. Digital tools now simulate grains, allowing virtual sandscapes to exist beyond touch. What remains constant, however, is the poetry of impermanence, the image is always about to vanish. These adaptations prove that sand, once bound to ritual ground, still evolves as a medium of time, rhythm, and fleeting beauty.

Sand animation begins with a flat, lit surface, often a glass topped lightbox. The artist sprinkles sand in controlled amounts, then moves it with fingers, palms, or tools to shape figures, landscapes, or abstract transitions. A camera placed above captures every shift, projecting the story in real time to an audience. Unlike static paintings, sand animation thrives on transformation, one image dissolves seamlessly into another, creating fluid motion. Music often accompanies the performance, amplifying its emotional resonance. The challenge lies not in precision but in rhythm, the artist must think in sequences, allowing each gesture to become both creation and erasure. This duality makes sand animation uniquely cinematic, as it combines live drawing, editing, and storytelling into a single performance. The process is less about permanence and more about the journey of watching forms rise, breathe, and fade, much like memory itself.

Technology has entered the grain. Some artists now use projectors and augmented reality to expand the possibilities of sand, layering digital light with organic texture. Others integrate sand art with theater, music, or dance, making it part of a multisensory experience. Eco conscious creators experiment with biodegradable pigments, reclaiming natural traditions in modern contexts. Digital sand apps allow anyone with a screen to play with ephemeral designs, democratizing the medium. Yet innovation is not only technological, it is also thematic. Artists use sand paintings to address climate change, migration, or identity, bringing relevance to a traditional form. These shifts prove that sand is not an outdated ritual but a material alive with reinvention. What was once sacred ground for ceremony now becomes a platform for global voices. Innovation, then, is not a departure but a continuation, sand still speaks, only in new languages.

Sand art captivates because it is time unfolding before the eye. In performances, audiences watch images being born and erased in one continuous flow. Unlike paintings that freeze, sand art moves, figures transform, landscapes shift, emotions ripple in rhythm with sound. Its fragility becomes its power, people know what they see will vanish, and that heightens its intensity. The live presence of the artist, hands constantly shaping and reshaping, creates intimacy, as if the audience is witnessing thought itself. Moreover, sand art requires no translation, its visual language speaks across cultures, making it suitable for global stages. Its popularity lies in this tension between control and surrender, permanence and impermanence, spectacle and silence. It is not just entertainment, it is a meditation disguised as performance, a reminder that beauty often exists in the very act of disappearing.

Sand paintings are born fragile. They are designed to dissolve, to teach impermanence, to leave memory rather than monument. This very essence creates challenges when cultures attempt to preserve them. Some traditions accept destruction as sacred, while museums and collectors seek methods of conservation, fixatives, photography, or re creations. The tension between preservation and ritual meaning defines the future of sand art. It is a heritage that resists permanence, reminding us that culture is not only what survives, but also what vanishes. The challenge is to honor both, the fleeting ritual and the lasting archive, without silencing the spirit of the art.

Destruction is not loss; it is completion. In Navajo and Tibetan traditions, sand paintings are never meant to last beyond their purpose. For the Navajo, once the patient has absorbed the healing, the painting is swept away so no one else can misuse its sacred power. For Tibetan mandalas, the act of dissolution embodies the teaching of impermanence: all forms, no matter how beautiful, are destined to end. This deliberate erasure is not tragic but liberating, reminding participants that attachment to form binds us to illusion. The destruction completes the ritual cycle, creation, use, release. By returning the sand to rivers, wind, or soil, traditions ensure that what was borrowed from the earth goes back to it. The painting lives not in permanence but in memory, in the lesson it carries, and in the shared experience of watching beauty vanish gracefully.

Museums face a paradox, how to keep what was meant to vanish. Some Navajo sand paintings are replicated using permanent pigments on boards or canvases, allowing symbolic designs to be studied without breaking taboos. Tibetan mandalas are often documented through photography, video, or recreated in colored powders for exhibitions, though always with consent from monastic authorities. In rare cases, fixatives are sprayed on sand to stabilize patterns, but this raises ethical questions, as it interrupts the tradition of impermanence. Many institutions now focus on preserving not the object but the process, through recordings, live demonstrations, or workshops. By shifting preservation from artifact to experience, museums attempt to balance respect for cultural values with the desire to archive. The sand itself may scatter, but the practice, knowledge, and story can be carried forward without betraying its essence.

The greatest challenge lies in contradiction, sand art resists conservation by its very nature. Fixing it undermines its spiritual or ritual significance, while letting it vanish denies future generations a direct encounter. Practical challenges include fragility, grains shift with vibration, humidity, or touch, and ethical questions about whether sacred practices should be displayed outside their context. Furthermore, conservation often risks reducing living traditions into static museum pieces, stripping them of their ritual breath. Another challenge is cultural appropriation, reproductions made without context can misrepresent or commodify sacred designs. Technology helps, high resolution imaging, digital reconstructions, even virtual reality, but these are only shadows of the original. Thus, the task is not only technical but philosophical, how do we honor impermanence while archiving knowledge? The solution may lie not in freezing the art but in preserving its cycle, ensuring that future generations witness both its making and its erasure.

Read More : A Complete Guide to Impasto Painting Styles and Materials

Sand paintings breathe in silence and dissolve in wind, yet they leave an eternal imprint in memory. Their fragility is their strength, their impermanence their permanence. Across continents, from the deserts of Navajo lands to the coasts of India, grains of sand arrange themselves into stories, prayers, and performances. What begins as ritual becomes heritage, and what dissolves becomes remembered. Festivals, pilgrimages, and global gatherings carry them forward, not as static art, but as living traditions. In recognition, the world does not preserve them by fixing them in frames, but by keeping them alive in practice.

Festivals unfold as living stages for sand painting traditions, where artistry is not only seen but shared. In India, mandalas and rangolis fill thresholds during Diwali, while Navajo ceremonies draw sand paintings as healing prayers. These celebrations are moments of collective witness, where hands move, colors spread, and patterns emerge only to vanish once the ritual is complete. The power lies in the act, not the endurance. Festivals ensure continuity by engaging both the community and the observer, reminding them that beauty can exist in the transient. Through music, storytelling, and ritual, sand paintings turn from solitary creations into public conversations, each festival becoming a moving archive of memory and identity. Thus, they preserve a fragile tradition not by shielding it, but by allowing it to flow into each generation’s rhythm.

Sand paintings are recognized as cultural heritage because they embody values that extend beyond visual form. They are rituals encoded in grains, carrying myths, prayers, and communal memory. UNESCO has acknowledged their heritage value not for their permanence, but for their ability to bind people together across time. These works speak of impermanence as a philosophy, where destruction is part of preservation, and disappearance is a kind of endurance. Communities guard them not in museums but in collective practice, by repeating, retelling, and re-creating. Recognition emerges because sand paintings are more than decorative expressions, they are acts of cultural survival, spiritual continuity, and social identity. They remind us that heritage is not always what we preserve in stone, but sometimes what we choose to dissolve in sand, only to be reborn again in rhythm with human gatherings.

Read More : Mastering Mural Art: Techniques, History, and Modern Practices

Sand art plays a dual role in tourism and global culture, it entertains and it educates. On beaches, competitions attract travelers who marvel at temporary sculptures, while in cultural festivals, sand paintings invite visitors into local traditions. Tourism finds in them both spectacle and storytelling, a moment of beauty that cannot be carried home except in memory. Globally, they act as cultural ambassadors, bridging diverse traditions from Tibetan mandalas to Mexican Day of the Dead altars. In an age that celebrates permanence, sand art introduces a counter narrative, valuing impermanence, humility, and presence. Its global recognition rests on this paradox, that the temporary can leave lasting impressions. By traveling beyond borders, sand art becomes both entertainment for the eye and meditation for the soul, shaping how cultures communicate values of heritage, spirituality, and creativity to the world.