Religious paintings began as more than art; they were acts of devotion. Early frescoes, mosaics, and cave depictions shaped spiritual memory. From Byzantine iconography to Renaissance painting, every period redefined how the sacred could be seen. Medieval art gave faith a visible language, and Baroque religious art added grandeur. These works were not passive visuals; they carried sermons, guided prayer, and anchored belief. What survives today is not only pigment but a timeline of faith expressed through brush, wall, and altar, marking the sacred journey of humankind through symbols and stories.

Religious paintings trace back to prehistoric cave art, where hunters painted animals as part of rituals. But the recognizable lineage of sacred art begins with ancient civilizations. Egyptian tomb murals, Greek temple frescoes, and Indian Ajanta caves show art bound to belief. By the early Christian era, icons became tools of worship. From the 4th century Byzantine icons, art became both theology and storytelling. By the Middle Ages, churches used vast murals and altarpieces as scripture for the illiterate. In essence, religious paintings began when art first carried prayer, shifting from survival magic to sacred narrative.

Civilizations saw painting as a bridge to the divine. Egyptians painted gods and afterlife scenes to guide the dead. Greeks painted myths on pottery and temple walls to honor deities. In India, early Buddhist cave paintings told stories of the Jataka tales, teaching moral lessons. Across cultures, paintings functioned as:

- Instructional tools: conveying spiritual lessons to common people.

- Ritual objects: aiding prayers, offerings, and ceremonies.

This use reflects an enduring truth, painting was not decoration, but invocation. The walls of caves, temples, and tombs were sanctified by color, carrying faith forward across centuries.

Medieval churches used art as scripture in visual form. With low literacy, medieval art made the Bible visible, saints, angels, Christ on crucifixions painted for teaching. Beyond instruction, art sanctified space: altarpieces radiated holiness, frescoes transformed stone into spiritual cosmos. Baroque religious art later expanded this with drama and emotion, guiding the faithful through awe. The Church understood art as theology without words, every mural a sermon, every icon a bridge to heaven. In emphasizing art, medieval churches ensured that faith wasn’t limited to scholars; it entered eyes, hearts, and memory of every worshipper who stepped inside.

Symbols in religious paintings are not ornaments but carriers of meaning. A Christian cross, a Hindu deity, or a Buddhist mandala each condenses theology into form. These symbols transcend literacy, turning faith into image. The cross speaks of sacrifice, mandalas guide meditation, Hindu gods embody stories of power and compassion. Even Islamic geometric art, avoiding figurative forms, creates visual devotion through rhythm and pattern. Across traditions, iconography unites worshippers, teaching faith through sight. These symbols endure because they function as memory, meditation, and map, pointing believers beyond the visible toward the eternal.

Christian art revolves around universal symbols. The cross embodies Christ’s sacrifice. The lamb recalls innocence and redemption. The dove signals the Holy Spirit. In Madonna and Child paintings, Mary symbolizes compassion and intercession. Saints carry identifying attributes, Peter with keys, Paul with a sword, allowing believers to “read” theology visually. In Gothic and Renaissance periods, light itself became a symbol: halos around saints or divine radiance streaming through stained glass. For worshippers, these weren’t decorative images but reminders of doctrine. Christian religious paintings therefore worked as visual catechism, offering believers not only beauty but guidance in faith.

Hindu deities appear not as abstractions but as vivid forms, each loaded with symbolism. Lord Vishnu often depicted reclining on the serpent Ananta, reflects cosmic order. Lord Shiva with trident and crescent moon embodies destruction and renewal. Maa Durga, mounted on a lion, signals strength against evil. Hands, weapons, and gestures (mudras) carry meaning, blessing, protection, wisdom. Traditional Indian schools like Pattachitra art or miniature painting crafted these divine forms with detail, linking mythology to devotion. In temples and homes, these images are not mere art, they are darshan, sacred sight, making the divine accessible to daily worship and ritual.

Read More : Exploring Botanical Paintings: Origins, Styles, and Preservation

Mandalas are not just intricate patterns, they are cosmic maps. A mandala reflects the Buddhist view of the universe, ordered, balanced, sacred. Painted on walls, scrolls, or sand, they serve meditation. For monks, drawing a mandala is itself a practice: every line an act of mindfulness. For practitioners, gazing at one becomes spiritual exercise, guiding the mind inward. Tibetan thangkas often feature mandalas centered on Buddha or deities, radiating outwards to symbolize enlightenment spreading into the world. Beyond aesthetic, mandalas function as both teaching and tool, a reminder that liberation lies in harmony and mindful vision.

Religious art wears local color. Indian miniature paintings told myths in jewel-like detail. Pattachitra art narrated Jagannath stories on cloth. Eastern Orthodox icons used stylized gold and stillness as portals to prayer. Tibetan thangka paintings served both meditation and pilgrimage offerings. Each tradition reflects faith filtered through geography, culture, and craft. While rooted in devotion, these works also preserved language, ritual, and identity. Religious paintings thus become both art history and anthropology, evidence of how different societies visualized the sacred while staying faithful to their own artistic languages.

Indian miniature paintings condensed epics and myths into vivid frames. From the Mughal courts to Rajput kingdoms, these works illustrated Bhagavata Purana, Ramayana, and Krishna’s leelas. Their small size made them portable, circulating stories of gods beyond temple walls. Fine brushwork and mineral colors gave sacred scenes durability and richness. Miniatures didn’t just decorate manuscripts, they taught bhakti, bringing divine stories into daily life. For patrons, they were symbols of devotion and prestige. For believers, they were darshan on paper. Their significance lies in how they democratized devotion, carrying divine narratives across regions and generations.

Tibetan thangkas are spiritual tools as much as paintings. Rolled like scrolls, they could travel with monks. A thangka usually depicts Buddha, bodhisattvas, or mandalas, serving as focus points for meditation. Practitioners use them for visualization, imagining themselves embodying compassion or wisdom. Painted with mineral pigments and gold, thangkas glow in ritual light, creating immersive meditation space. Beyond private practice, thangkas are unfurled during festivals, transforming community worship. Their function is dual: inward, guiding meditation; outward, teaching dharma. This balance makes them vital to Tibetan Buddhism, blending aesthetics, theology, and practice into one sacred medium.

Icons in Eastern Christianity are not simply images but windows into the divine. Painted according to strict canons, an icon is theology in color. Saints and Christ are depicted front-facing, with solemn eyes, to invite direct spiritual connection. The use of gold leaf symbolizes divine light. Believers venerate icons not as objects but as presences, channels of prayer. In liturgy, icons structure space, lining iconostases, adorning altars, sanctifying homes. Their centrality rests on their role as mediators, bridging earth and heaven, individual and community, material and spiritual. For Orthodox Christians, icons are both art and sacrament.

Religious paintings were never just images; they were born from precise techniques and rare materials. Every stroke carried both artistic skill and devotional purpose. Fresco, tempera, oil, and gold leaf gave depth, brilliance, and permanence to scenes of gods, saints, and sacred rituals. Natural pigments, ground from minerals and plants, carried symbolic weight. Lapis lazuli for divinity, vermilion for vitality. Indian devotional paintings used organic colors prepared with ritual purity, while European masters turned walls and panels into enduring spiritual narratives. The materials themselves became part of the prayer, transforming paintings into sacred objects that resonated through time.

Fresco painting transformed Renaissance churches into immersive sanctuaries. Artists like Michelangelo and Giotto applied pigment directly onto wet plaster, fusing color with wall surfaces. This method allowed vast biblical narratives to unfold across domes and chapels. Fresco demanded speed and precision, the pigment dried quickly, making every brushstroke permanent. But its permanence gave sacred stories a monumental presence. Visitors did not just view these works, they entered them, surrounded by scripture in visual form. Fresco united architecture, theology, and artistry, creating spaces where faith and art coexisted. The technique defined Renaissance spirituality by embedding belief within stone itself.

Gold leaf was more than a decorative choice, it symbolized divine light. Medieval icon painters applied wafer thin sheets of gold to halos, backgrounds, and sacred garments. The reflective surface created a glow that shifted with candlelight, making holy figures seem alive and radiant. In Christian theology, gold suggested heaven’s eternal brilliance, untouched by earthly decay. Technically, applying gold leaf was painstaking, sheets adhered with gesso or bole and were burnished to mirror like shine. In Orthodox and Catholic traditions, these icons functioned not just as images but as mediators of prayer. The shimmer of gold drew worshippers into spiritual contemplation.

Indian devotional paintings relied on natural and symbolic materials. Artists used:

- Vegetable dyes from indigo, turmeric, and madder.

- Mineral pigments like malachite green and lapis blue.

- Gold powder for divine halos and ornaments.

In Pattachitra and Tanjore styles, pigments were prepared ritually, sometimes blessed before use. Surfaces ranged from cloth to palm leaf, each chosen for durability and spiritual resonance. Cow dung and lime bases were common for walls, creating textures that absorbed color deeply. These materials aligned with the philosophy of sattva, purity and natural balance. Every hue carried meaning: red for energy, white for peace, blue for cosmic power. Thus, material and message were inseparable, turning the painting into a spiritual vessel rather than mere decor.

Religious paintings today reflect a shift from rigid tradition to fluid interpretation. Contemporary artists use abstraction, mixed media, and cross cultural motifs to speak to a global audience. Sacred narratives are no longer confined to churches or temples, they appear in galleries, homes, and digital canvases. Modern Hindu art blends myth with modern aesthetics, while Christian artists experiment with abstraction to capture spirituality beyond form. Interfaith art bridges traditions, creating a dialogue between cultures. This evolution reflects not a loss of faith but a search for new ways to express it, ensuring religious art remains both timeless and contemporary.

Modern artists reinterpret faith by fusing tradition with individuality. Instead of repeating classical forms, they emphasize personal encounters with the divine. For example, Indian painters depict Krishna in vibrant pop art styles, while Christian artists use abstract brushwork to evoke spiritual awe without literal figures. Global exhibitions highlight hybrid works where Islamic geometry meets digital light installations. This shift broadens access, sacred art becomes relatable beyond its immediate community. Yet, the emotional weight remains, modern reinterpretations still aim to inspire reflection, reverence, or inner stillness. The essence of worship adapts, carried forward through innovation while rooted in inherited narratives.

Abstraction offers a universal language for spirituality. Shapes, colors, and textures bypass doctrine, reaching directly into emotion. Artists turn to abstraction to suggest the ineffable, the part of divinity words and figures cannot capture. For instance, Mark Rothko’s vast canvases in deep hues invite meditative silence, functioning almost as modern altarpieces. In Hindu and Buddhist traditions, abstract motifs like mandalas already carried spiritual symbolism, so contemporary painters extend this lineage. The blend also mirrors modern life, where spirituality often transcends single faith systems. Abstraction makes sacred art accessible, inclusive, and resonant for viewers navigating diverse, complex identities.

Interfaith art has become a bridge between cultures. In a world often divided by belief, these works highlight shared values, compassion, transcendence, unity. Paintings combine elements like the Christian cross with the Hindu lotus or Islamic geometry with Buddhist mandalas. Such synthesis does not dilute meaning, it enriches it. Exhibitions in global cities celebrate these overlaps, positioning religious art as a platform for dialogue. For communities, interfaith art offers healing, reminding them of interconnected spiritual heritage. Beyond aesthetics, these works function as cultural diplomacy, using color and form to express harmony. Today, interfaith art speaks louder than sermons.

Religious paintings are not just aesthetic objects, they live within ritual practice. In temples, they guide devotees through stories of gods. In churches, they serve as altarpieces, focal points of worship. Pilgrimage sites sell painted souvenirs, carrying sacred memory into daily life. Each function emphasizes connection, between human and divine, community and tradition. Beyond ritual, these works shape cultural identity. They preserve myths, document festivals, and reinforce collective memory. To understand religious paintings is to see how art intertwines with lived spirituality, becoming both medium and message. They are not silent on walls, they participate in worship itself.

Temples and churches weave paintings directly into ritual practice. In Hindu temples, murals narrate epics like the Ramayana, guiding devotees from entrance to sanctum. These visuals align with chants, creating a multi sensory devotion. In Catholic churches, paintings frame the altar, serving as focal points during Mass. Stations of the Cross, painted on walls, help worshippers meditate on Christ’s suffering. Icons in Orthodox traditions are kissed, lit with candles, and carried in processions. Across faiths, paintings are not passive, they orchestrate movement, prayer, and memory. They act as companions to ritual, transforming spiritual acts into embodied, visual experiences.

Altarpieces are central to Christian liturgy. Positioned behind the altar, they frame the Eucharist, the core of worship. These panels often depict the Last Supper, Virgin Mary, or saints, reminding worshippers of sacred narratives while sacraments unfold. During the medieval and Renaissance eras, artists like Jan van Eyck designed polyptychs that opened and closed with the liturgical calendar. The use of scale, perspective, and symbolism drew the eye heavenward, reinforcing divine presence. Today, altarpieces continue this role, whether ornate Gothic carvings or minimalist abstract panels. They focus attention, guide prayer, and embody the visual heart of Christian ritual.

Paintings act as memory vessels in pilgrimages. Pilgrims often carry small painted icons or scrolls as souvenirs of sacred journeys. These objects extend the pilgrimage experience into everyday life, serving as reminders of devotion and endurance. In places like Varanasi or Santiago de Compostela, religious art is not just bought, it is blessed, binding the traveler to the holy site. For local communities, selling these works sustains craft traditions and livelihoods. Pilgrimage paintings also spread culture, a small Pattachitra or icon carried abroad introduces local spiritual narratives globally. They embody both personal devotion and cultural continuity.

Religious paintings are not only visual treasures but also cultural memory capsules. Their preservation demands art conservation techniques that balance age old traditions with modern science. From climate controlled galleries to digital archiving, every effort ensures fragile pigments and natural materials withstand time. Museum curation plays a central role, often showcasing restored pieces alongside contextual stories. Private collections too, contribute to the safeguarding of sacred art, though access is often limited. Globally, bodies like UNESCO classify certain works as heritage, underlining their universal value. The takeaway is simple, preservation protects faith narratives that connect centuries and communities.

Museums approach the preservation of ancient religious paintings with layered care. They monitor temperature, humidity, and light levels to minimize deterioration of pigments and canvas. Restorers often use reversible methods, ensuring any treatment can be undone in the future. For fragile works, protective glazing and specialized mounts prevent physical damage. Equally important is documentation, detailed imaging, chemical analysis, and historical records that capture the painting’s present state. Some institutions create replicas for public display, keeping originals secure in archives. This balance between accessibility and protection reflects museum curation’s dual responsibility, honoring the artwork’s devotional meaning while safeguarding its physical existence for generations.

UNESCO designates certain religious paintings as heritage because they represent more than artistry, they embody shared human values, faith systems, and cultural continuity. For example, murals in Ajanta are recognized not only for their Buddhist symbolism but also for their innovation in technique and storytelling. These works transcend local worship, influencing global understanding of spirituality, aesthetics, and history. UNESCO protection ensures international cooperation in conserving them, offering funding, expertise, and policy support. Such recognition also highlights their fragility, from natural decay to threats like urban expansion. When classified as heritage, these paintings gain status as collective cultural property, reinforcing their timeless relevance.

Conserving devotional art presents unique difficulties. First, materials such as mineral pigments, organic binders, or fragile fresco surfaces react unpredictably to environmental changes. Second, context matters, removing a temple mural from its sacred site risks losing its ritual meaning. Third, funding and expertise remain uneven, especially outside major institutions. Religious sensitivities also complicate conservation, altering or relocating a sacred piece may spark controversy. Political instability and illegal trafficking further endanger such works. Despite advances in art conservation, these challenges persist. Successful preservation demands collaboration between scientists, faith communities, and cultural bodies, balancing material survival with respect for spiritual integrity.

Religious paintings reveal the soul of faith traditions. They are not merely visual representations but tools of teaching, worship, and cultural bonding. Christianity used them to tell biblical stories to largely illiterate communities. Hinduism embraced divine storytelling with vibrant symbolism, each deity depicted with attributes that communicated cosmic order. Buddhism used murals to spread teachings across Asia, while Sikhism employed art sparingly yet meaningfully in scriptural contexts. Islam, with its calligraphic strength, restricted figural representation but embraced geometric and floral patterns as spiritual symbols. Judaism too, leaned toward symbolic artistry. Collectively, these traditions illustrate how art mediates between the divine and human.

Christianity employs painting as a profound medium of faith expression. Early frescoes in catacombs provided comfort to persecuted believers, blending secrecy with devotion. Later, medieval and Renaissance art flourished with iconic images of Christ, the Virgin Mary, and saints that served both as theological teaching and spiritual inspiration. Works such as Giotto’s frescoes or Raphael’s Madonna and Child carried visual clarity that resonated with lay audiences. Paintings also reinforced liturgy, altarpieces framed worship with biblical narratives. Beyond churches, private devotional panels shaped personal spirituality. Across centuries, Christian paintings evolved from symbolic simplicity to dramatic realism, yet their core aim remained, making the unseen visible and guiding hearts toward belief.

Hindu art thrives on visual storytelling because mythology is vast, layered, and symbolic. Paintings became mnemonic devices, retelling epics like the Ramayana and Mahabharata. They employed color codes, gestures, and iconography such as blue signifying divinity, multiple arms denoting cosmic power, lotus representing purity. This form of narrative art was accessible to communities with diverse literacy levels. It also blended seamlessly with temple architecture, festivals, and rituals, making stories immersive experiences. Through murals, miniature paintings, or Pichwai art, devotees engaged directly with the divine narrative. In Hindu culture, art was not decorative but participatory, bridging gods and mortals through imagery that spoke to both eyes and soul.

Certain artists shaped the way humanity visualized faith. Michelangelo’s ceiling in the Sistine Chapel remains one of the most ambitious depictions of biblical cosmology. Leonardo da Vinci captured sacred intimacy and psychological depth in The Last Supper. Raphael humanized divine figures with warmth and elegance. In India, Raja Ravi Varma redefined mythological art, blending European realism with Indian narratives. Giotto, often called the father of Renaissance painting, introduced emotional realism to sacred stories. These artists not only shaped religious imagination but also bridged theology and humanism. Their works continue to inspire awe, worship, and artistic exploration worldwide.

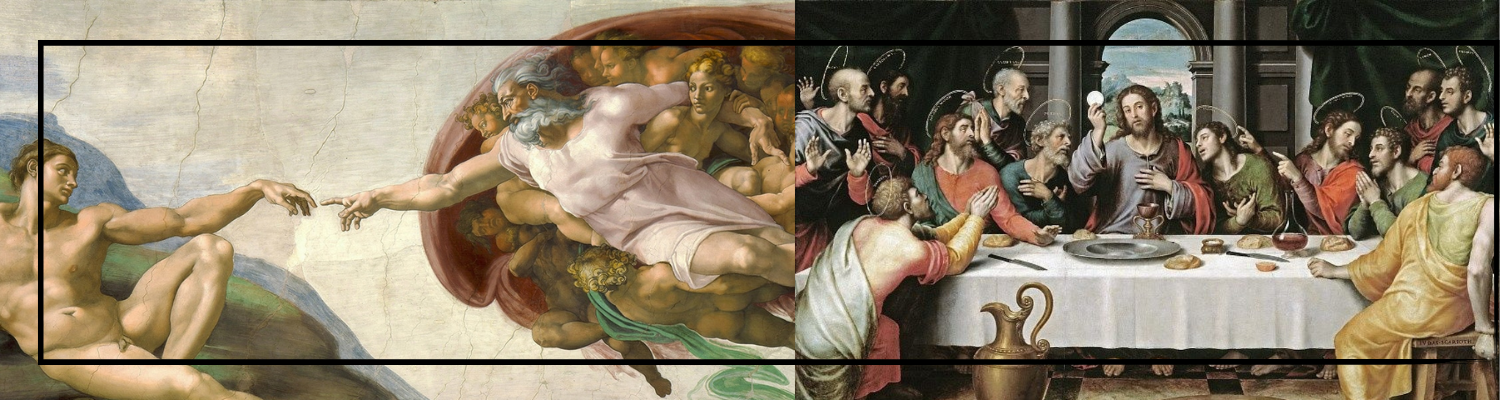

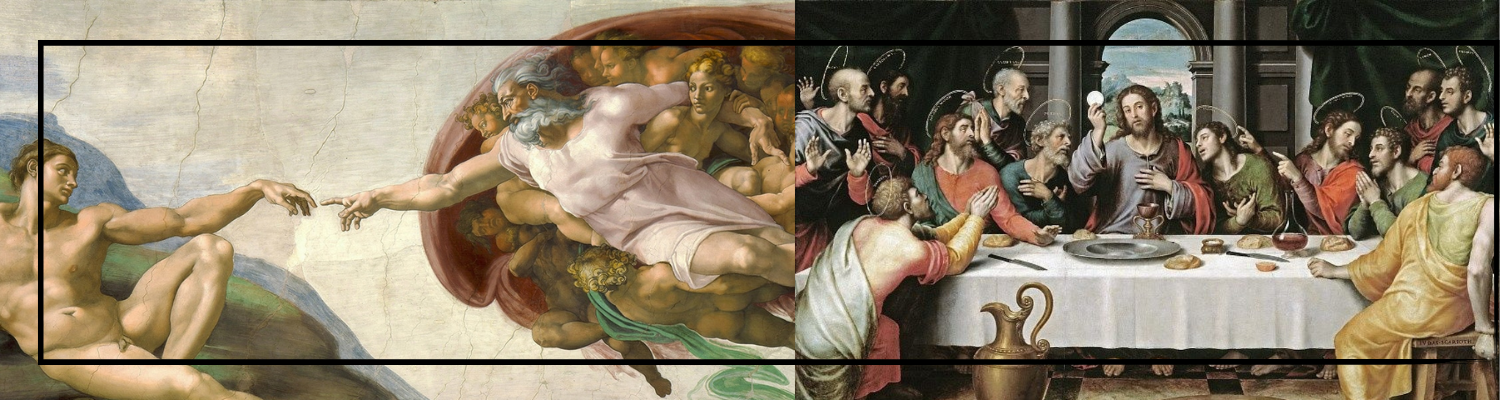

Michelangelo’s religious paintings are monumental in both scale and impact. The Sistine Chapel ceiling painted between 1508 and 1512 depicts Genesis stories from Creation to Noah’s Flood using muscular figures that conveyed divine drama. The Creation of Adam, where God and man nearly touch fingertips, became an enduring symbol of human potential. Later, The Last Judgment on the chapel’s altar wall redefined eschatological art, presenting salvation and damnation with unflinching realism. Michelangelo’s use of anatomy, perspective, and dramatic tension transformed how sacred narratives were imagined. His works were not passive images but immersive experiences, inviting viewers to confront divine mystery and human destiny simultaneously.

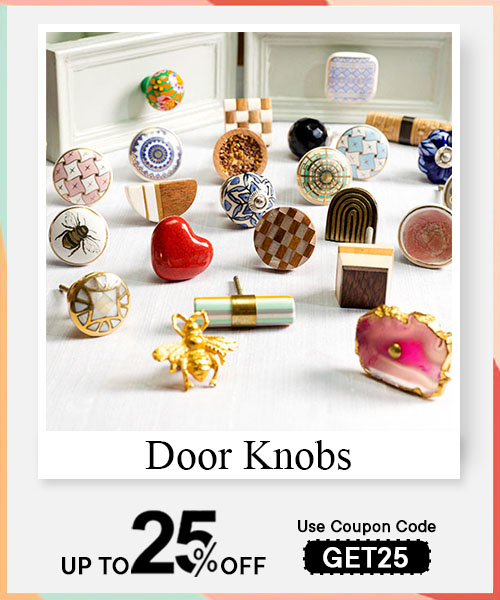

Leonardo’s Last Supper stands apart because it captured not just a biblical moment but the psychology of faith. Painted on the refectory wall of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, it shows the instant Christ reveals betrayal among his disciples. Each apostle reacts differently, shock, denial, anger, reflecting Leonardo’s study of human emotion. Unlike earlier static versions, his composition was dynamic, with perspective lines drawing attention to Christ’s calm center. The painting blended science, art, and theology, setting new standards for religious imagery. Though fragile due to experimental techniques, its cultural and spiritual resonance endures. It is less a painting and more a meditation on trust, betrayal, and grace.

Raja Ravi Varma revolutionized Indian religious art by merging Western realism with Hindu mythology. Before him, religious art largely thrived in traditional styles like miniature or folk painting. Varma used oil on canvas, a European medium, to bring gods and goddesses into lifelike presence. His Saraswati, Lakshmi, and Shakuntala became iconic images, shaping how modern India visualized its deities. Importantly, he democratized sacred art by using lithographs, making affordable prints accessible to households across India. This widened devotional engagement beyond temples, embedding art into domestic spaces. His work bridged cultures, making Indian mythology resonate with modern visual sensibilities while retaining its spiritual depth.

Famous religious paintings are more than masterpieces, they are cultural mirrors. The Last Supper portrays trust and betrayal, urging reflection on loyalty. The Sistine Chapel ceiling narrates the creation story in cosmic scale, a testament to human divine connection. Madonna and Child paintings universalize maternal love, making spirituality intimate. Ajanta murals embody Buddhist compassion and the path to enlightenment. These works show how faith travels through images, making abstract doctrines tangible. Their meanings endure not just because of technique, but because they address eternal human questions such as life, death, morality, and redemption. Art here becomes theology painted in color, emotion, and form.

The Last Supper illustrates the biblical moment from the Gospel of John when Jesus shares his final meal with his disciples. Central to the scene is Christ announcing that one among them will betray him. Leonardo arranged the apostles in groups of three, each responding with unique gestures, some recoiling in disbelief, others leaning forward in questioning. Judas, clutching a money bag, is subtly set apart in shadow. Christ remains serene at the center, symbolizing divine acceptance. This narrative painting blends drama with symbolism, bread and wine foreshadow the Eucharist, while perspective lines emphasize Christ as the spiritual anchor. Its story is not merely historical, it dramatizes loyalty, sacrifice, and the tension between human weakness and divine purpose.

The Sistine Chapel ceiling is a masterpiece because it integrates theology, artistry, and humanism on an unprecedented scale. Commissioned by Pope Julius II, Michelangelo painted over 300 figures across nine central panels narrating Genesis, surrounded by prophets, sibyls, and ancestors of Christ. The Creation of Adam, with its iconic near touch, epitomizes humanity’s relationship with God. Unlike static medieval art, Michelangelo’s dynamic figures radiated vitality, embodying divine grandeur. The ceiling fused sculptural anatomy with painterly vision, reshaping Western art’s trajectory. Its religious depth lies in its scope, it is not a single story but the drama of creation, fall, and hope, captured in a unified cosmic vision that still compels worshippers and visitors alike.

Ajanta murals painted between the 2nd century BCE and 6th century CE serve as visual sermons of Buddhism. They depict Jataka tales, stories of the Buddha’s past lives, teaching virtues like compassion, sacrifice, and mindfulness. The paintings use gentle expressions, flowing lines, and earthy palettes to emphasize serenity and moral clarity. Scenes of Bodhisattvas, adorned with ornaments yet radiating spiritual calm, highlight the path of renunciation balanced with worldly compassion. The cave interiors, lit once by oil lamps, created immersive environments for meditation. Beyond art, these murals reflect Buddhism’s spread along trade routes, connecting spiritual practice with cultural exchange. They remain living lessons on impermanence, empathy, and inner awakening.

Religious paintings have long acted as visual scriptures, bridging oral traditions with imagery. In temples, churches, and monasteries, paintings narrated stories from epics and sacred texts. They served as a medium of visual catechism, helping communities understand complex theology without written words. Murals in cathedrals illustrated biblical stories, while temple frescoes captured mythological narratives. This visual teaching reinforced values, morality, and collective identity. For illiterate communities, paintings were not only art but also accessible education. They taught ethics, rituals, and spiritual ideals. Today, these works still remind us that art is a living textbook of devotion.

Paintings simplified vast narratives into visual lessons. In medieval Europe, frescoes of biblical scenes explained the Gospels to congregations. In India, epics like the Ramayana and Mahabharata were painted on temple walls, helping devotees internalize stories. Religious paintings acted as visual catechism, combining theology with artistic symbolism. Their colors, gestures, and settings conveyed moral clarity. For instance, halos marked divinity, hand gestures showed blessings, and landscapes set the spiritual stage. These details made stories both engaging and memorable. They carried wisdom from one generation to the next without relying on literacy, ensuring sacred teachings endured in public memory.

Murals spoke a universal language of color, form, and gesture. In societies where literacy was rare, they acted as a collective classroom. Church walls covered with biblical murals offered entire communities access to sacred narratives during Mass. In India, temple murals of gods and mythological scenes guided devotees through stories without requiring texts. Their scale, symbolism, and accessibility created shared understanding.

- Preserve cultural memory across generations

- Build collective identity through shared imagery

- Teach values, morals, and rituals visually

Murals ensured that devotion and education merged into one seamless spiritual experience, leaving lasting impressions on entire communities.

Visual narratives act as a bridge between faith and imagination. A devotee standing before a painting of Madonna and Child or Krishna with Radha does not just see form, but feels intimacy with divinity. These images encourage meditation, strengthen memory of stories, and guide rituals. The act of gazing itself becomes prayerful. In Buddhist mandalas, patterns lead the mind toward transcendence, while Christian icons invite inner dialogue with saints. Such works go beyond illustration. They shape emotional and spiritual connection, reminding believers that devotion is not only spoken in words but also visualized in art, color, and light.

Religious paintings were not isolated from broader art history. They acted as catalysts for major movements. Gothic art brought sacred grandeur through stained glass and elongated forms. Renaissance humanism emphasized realism and humanity in divine figures, reflecting a shift toward earthly presence in sacred art. Romanticism reinterpreted religious themes with emotion and awe. Symbolism used mystical imagery to explore spirituality, while Modernism questioned tradition yet retained echoes of sacred symbolism. Each movement carried forward religious influences, adapting them to new contexts. The result is a layered dialogue between devotion, aesthetics, and cultural transformation.

Renaissance humanism placed human dignity and reason at the center of culture. Religious paintings shifted from flat symbolic styles to naturalistic representation. Artists like Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo portrayed Christ, Mary, and saints with lifelike anatomy and human emotion. This reflected a theology that embraced both divine and human nature. Biblical scenes unfolded in realistic settings with architectural depth and perspective, bridging heaven and earth. Religious paintings became not only devotional but also intellectual works, inviting contemplation of faith and humanity together. This reshaping left an enduring mark on global visual culture.

Romanticism placed emphasis on emotion, mystery, and awe. Religious paintings during this period moved away from rigid doctrine and embraced imagination. Biblical and mythological themes were painted with stormy skies, dramatic light, and deep emotion, conveying the sublime power of the divine. Artists sought to awaken spiritual wonder rather than strict adherence to theological accuracy. Romantic religious art often depicted man’s smallness against divine majesty. By emphasizing feeling over form, Romanticism offered a more personal, emotional connection to sacred themes, influencing how later generations engaged with religion through art.

Modern art questioned traditions, but symbolism from religion never disappeared. Abstract forms, surrealist images, and minimalist icons still borrowed from sacred language. The cross, mandala, lotus, or halo reemerged in reinterpreted ways, reflecting spirituality beyond institutional boundaries. Religious symbolism in modern art often invites personal interpretation rather than collective ritual. Artists used these symbols to address themes of transcendence, alienation, or divine search in contemporary life. This shows how sacred imagery adapts yet remains central in exploring human meaning. Even stripped of ritual, symbols carry deep resonance in cultural imagination.

Read More : Best Wall Designs That Will Inspire You to Revamp Your Home

Religious paintings are more than aesthetic works. They are tools of transcendence and inner reflection. A sacred painting can calm the restless mind, ignite spiritual longing, or act as a meditative focus. In monasteries and temples, paintings align the senses toward devotion. The psychological pull of color, symmetry, and form creates both awe and intimacy. For believers, these works embody sacred presence. For non-believers, they offer windows into universal human longing for meaning. Their impact lies in bridging the external act of viewing with the internal experience of spirituality.

Paintings evoke emotions by combining form, symbolism, and sacred presence. A Christian icon of Christ Pantocrator or a Hindu painting of Vishnu radiates both authority and compassion through visual cues. Colors carry meaning, blue for divinity, gold for eternity, red for power. Composition guides the gaze, encouraging focus and reverence. For believers, this awakens emotions of love, humility, or awe. For the viewer, the act of contemplation itself becomes prayerful. Paintings embody silence, depth, and transcendence, reminding us that art is not only to be seen but to be felt at a spiritual level.

Religious artworks act as visual anchors for the mind. In Buddhism, mandalas are used to focus thought and guide meditation toward transcendence. In Christianity, icons offer a still point for prayer, centering the believer in presence. Hindu devotional paintings of deities serve as focal points for visualization, helping devotees internalize divine attributes.

- Symbolic patterns that calm the mind

- Sacred imagery that awakens devotion

- Ritual practice connecting sight with inner stillness

Artworks transform passive viewing into active contemplation, making them essential tools for both personal and communal spirituality.

Icons function as living presences within sacred spaces. For believers, they are not mere images but gateways to the divine. The psychological effect is profound, icons reduce anxiety, strengthen faith, and create a sense of divine nearness. In Orthodox tradition, kissing or touching an icon builds intimacy with the sacred. The stillness of the image mirrors inner stillness. Colors, gestures, and faces communicate beyond words, fostering emotional resilience and spiritual comfort. Icons remind believers that the divine is accessible, immediate, and personal. Their psychological power lies in merging image, faith, and inner healing.

Religious paintings are no longer confined to temples or cathedrals. They live in the heart of modern homes as wall art, altars, and focal points of interior design. A Krishna canvas in the living room or a Madonna icon in a study becomes more than decoration, it signals values, belief, and continuity with heritage. In urban apartments, sacred art balances modern minimalism with spiritual grounding. It carves out sanctuaries of calm in everyday life. Beyond style, these works remind residents of prayer, devotion, and identity. They connect the intimacy of the home with timeless cultural traditions.

Religious paintings are used to blend sacred presence with aesthetic harmony. Homeowners hang them in living rooms, dining areas, and personal sanctuaries where art becomes a silent anchor of faith. A framed Ganesha painting at the entrance symbolizes protection, while a cross above a bed speaks of blessing. These works complement interior design, fitting into contemporary palettes yet carrying eternal resonance. They are often chosen for color balance, spiritual symbolism, and emotional comfort. In modern homes, the sacred does not overpower decor but integrates seamlessly, giving interiors a layered meaning. Every painting becomes a dialogue between tradition and lifestyle.

Placing devotional art in private rooms reflects intimacy with faith. While public spaces may display grandeur, personal areas favor closeness. People choose paintings of deities, saints, or sacred symbols to create an atmosphere of comfort and reflection. The practice responds to emotional needs:

- Offering reassurance in times of stress

- Providing a focus for prayer or meditation

- Creating continuity with family traditions

A painting near a study desk may inspire ethical focus, while one near a dining table fosters gratitude. These spaces remind individuals that spirituality is not external alone, but part of daily rhythm.

Read More : The Art of Sand Painting: Rituals, Materials, and Global Traditions

Religious decor preserves cultural identity in a rapidly globalizing world. A Sikh family in London may display a Guru Nanak painting as a connection to heritage. A Buddhist household in California may use mandalas as both design and devotion. Such art does more than fill walls, it anchors memory, ancestry, and belonging. The motifs, colors, and stories carried in these works transmit heritage across generations. They signal to guests where values are rooted, while offering residents an inner compass. Religious decor allows identity to be lived daily, not just remembered, bridging cultural pride with personal spirituality.