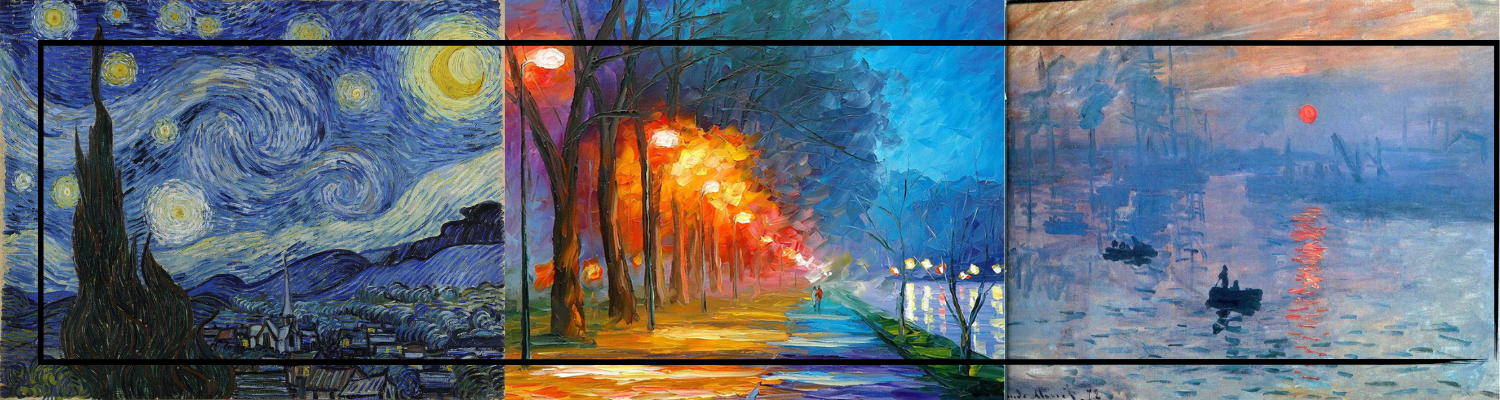

Impressionist painting began in the late 19th century, in France, when artists broke away from academic traditions that valued polished finish and historical grandeur. The movement rose from a mix of rebellion and cultural shift. Painters such as Claude Monet and Édouard Manet rejected rigid structures of the Paris Salon, turning instead to fleeting light, ordinary scenes, and personal perception. Impressionism was not just an artistic style, it was a protest against conformity. Born in cafés, studios, and riversides, it captured both the pulse of modern Paris and the timeless beauty of nature.

The birth of Impressionism cannot be separated from the political and cultural climate of 19th century France. After the Franco Prussian War (1870–71) and the upheaval of the Paris Commune, the city underwent vast urban redevelopment under Baron Haussmann. Wide boulevards, bustling cafés, and new leisure spaces became fresh subjects for artists tired of mythological and religious scenes. Meanwhile, the Industrial Revolution brought new pigments, portable paint tubes, and faster travel, allowing artists to explore open air landscapes. Equally important was the decline of academic authority, as younger painters grew frustrated with the Paris Salon’s rigid selection. Impressionism emerged as both a reflection of and response to this rapid transformation of society. The movement embodied freedom, freedom of vision, freedom of subject, and freedom of expression. Impressionist painters thus stood at the intersection of politics, technology, and modern identity, recording a world in transition with each brushstroke.

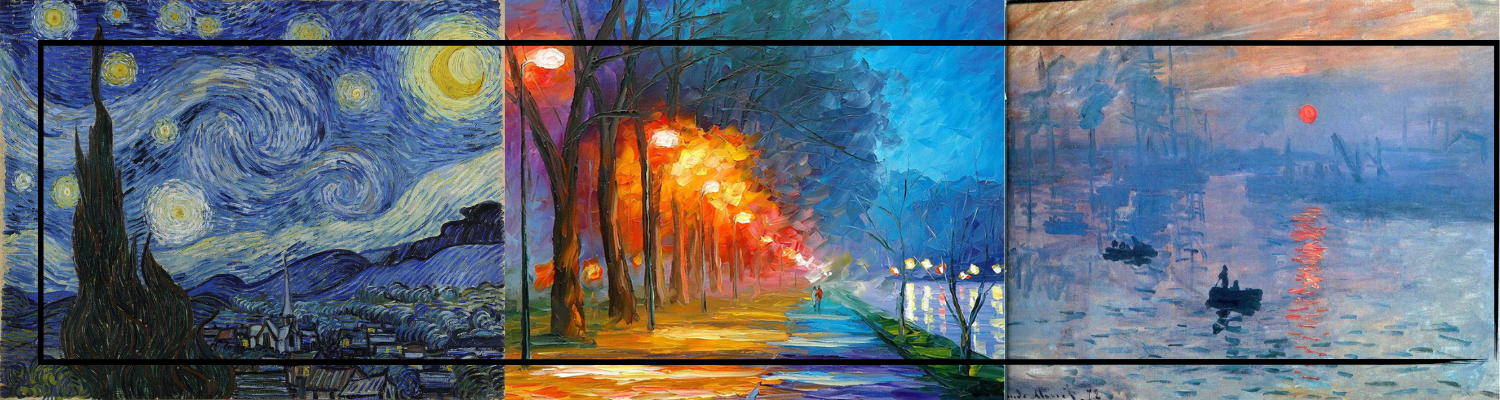

Claude Monet is often considered the heartbeat of Impressionism. His painting Impression, Sunrise (1872) gave the movement its very name, capturing a fleeting moment in Le Havre harbor with loose strokes and shimmering light. Monet challenged the notion that art must idealize. Instead, he presented reality as it appeared, transient, unfinished, alive. He pioneered plein air painting, working outdoors to study changing sunlight across hours and seasons. His series paintings, like the Haystacks or Rouen Cathedral, showed how perception alters with time, proving that light is never static. Monet also influenced group exhibitions, encouraging artists to bypass the Salon and showcase independently. By doing so, he helped solidify Impressionism as a collective rebellion, not just an isolated style. His philosophy was simple yet revolutionary, to see with fresh eyes and to honor the fleeting over the permanent. Monet turned impermanence into the very soul of modern art.

Read More : Exploring Botanical Paintings: Origins, Styles, and Preservation

The Paris Salon, controlled by the Académie des Beaux Arts, upheld strict standards of finish, narrative, and grandeur. Early Impressionist works, loose brushstrokes, visible texture, ordinary subjects, appeared unfinished and vulgar to jurors. For instance, Manet’s Olympia (1865) scandalized critics with its frank portrayal of a nude woman. Monet’s landscapes, Renoir’s gatherings, and Degas’s dancers seemed too mundane, lacking “nobility.” The Salon valued history painting, smooth polish, and moral storytelling, while Impressionists embraced immediacy and modernity.

- The Salon saw Impressionists as unprofessional experimenters.

- Their works challenged the institution’s cultural authority.

This rejection, however, fueled innovation. In 1874, artists staged the First Impressionist Exhibition, showing their defiance by creating a parallel stage for art outside official approval. Ironically, what the Salon dismissed as “unfinished sketches” would later define modern painting, proving that innovation often requires confrontation. The Salon’s rejection, rather than silencing them, gave Impressionists their voice.

Impressionist painting revolutionized how artists engaged with color, light, and perception. At its core, it was less about detail and more about sensation. Painters abandoned heavy outlines and smooth blending, replacing them with quick brushstrokes, vibrant color contrasts, and optical mixing. They sought to mirror the human eye’s fleeting impressions, capturing not just what was seen but how it was felt. The technique of plein air painting made landscapes breathe with authenticity. Impressionism’s methods blurred science and emotion, drawing on color theory while elevating the beauty of everyday life. This fusion of intellect and spontaneity remains its signature.

Several defining techniques distinguish Impressionism from prior art. The most critical is the visible, broken brushstroke, which gave surfaces a shimmering, dynamic quality. Instead of layering glazes, artists used pure, unmixed colors, letting the viewer’s eye blend them through optical mixing. Light became the true subject, reflections on water, shifting skies, or dappled leaves. Shadows were painted not in black, but in blues, purples, and greens, echoing discoveries in color theory. Importantly, Impressionists embraced open compositions, cutting scenes abruptly like photographs, a nod to modernity. Everyday subjects, from bustling Paris cafés to quiet riverbanks, gained dignity through these methods. The effect was not to reproduce reality in detail, but to recreate the sensation of being there. Impressionist techniques were revolutionary because they aligned with the rhythm of life itself, fragmented, shifting, and luminous. They democratized art, allowing the ordinary to shine with extraordinary vitality.

Short, fragmented brushstrokes are central to Impressionism’s visual rhythm. By leaving strokes visible, painters conveyed the immediacy of perception, as if the viewer were glimpsing a moment before it vanished. These strokes break down forms into fragments of light and color, imitating how the human eye perceives rather than how the hand polishes. In Monet’s Water Lilies, the strokes ripple across the canvas, echoing movement in water. In Renoir’s dance scenes, strokes flicker like fleeting gestures in crowded rooms. Unlike polished classical art, which freezes time, these marks vibrate with continuity, hinting at what came before and after the scene. The eye actively participates, blending strokes into motion, creating a sense of life beyond the frame. This technique not only revolutionized artistic practice but also mirrored the modern world, full of speed, flux, and uncertainty. Through brushstroke, Impressionists taught us to see time itself on canvas.

Plein air painting was both a practical and philosophical choice. With portable paint tubes, artists could leave studios and immerse themselves in nature. Outdoors, they could study shifting sunlight, atmospheric changes, and how colors transformed through the day. For Monet, Pissarro, and Sisley, this practice allowed direct engagement with light’s impermanence. Urban scenes also benefited, boulevards, gardens, riversides reflected the rhythms of modern Paris.

- Authentic representation of light and weather.

- Spontaneity and immediacy in color.

- Freedom from academic studio rules.

Culturally, plein air painting aligned with broader movements toward individuality and freedom in post Haussmann Paris. It turned ordinary spaces into subjects worthy of art. For Impressionists, painting outdoors was not only about technique but also about philosophy, art should mirror life as it is lived, in fragments, in motion, under changing skies. The open air was their true studio.

Impressionism was never a single voice but a chorus of perspectives. Alongside Monet, artists such as Pierre Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, Berthe Morisot, Camille Pissarro, and Mary Cassatt brought unique tones. Renoir painted warmth in social gatherings, Degas captured the precision of dancers, and Pissarro chronicled rural labor with empathy. Women like Morisot and Cassatt fought barriers to leave lasting marks on the movement. Each artist shaped Impressionism into more than a style, it became a cultural lens on leisure, labor, and intimacy. Their works carried Impressionism beyond rebellion, making it a foundation for modern art’s diversity.

The “core circle” of Impressionists included Claude Monet, Pierre Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, Camille Pissarro, and Berthe Morisot, with Mary Cassatt bridging Europe and America. Monet remains the movement’s emblem, pioneering landscapes and light studies. Renoir celebrated human connection through scenes of leisure, dances, and gatherings. Degas captured the discipline of ballet dancers with analytical sharpness. Pissarro was both painter and mentor, guiding younger artists and experimenting with rural subjects. Morisot and Cassatt offered a vital counterpoint, focusing on domestic life, intimacy, and women’s experiences, often overlooked in the male gaze. Together, these artists formed a collective that challenged the Paris Salon and redefined modern painting. Their diversity of subjects, ranging from bustling boulevards to private interiors, made Impressionism universal in scope. These names still anchor museums, textbooks, and cultural imagination, standing as the pillars of an art movement that broke barriers with light and immediacy.

Women like Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt redefined Impressionism from within. Restricted from cafés and public studios, they turned inward, painting domestic interiors, family, and motherhood, subjects often dismissed by male critics. Their work challenged hierarchies by giving weight to overlooked experiences. Morisot’s airy brushwork captured fleeting emotional states, while Cassatt portrayed women not as objects but as active participants in modern life. They also gained recognition in Impressionist exhibitions, pushing boundaries despite social constraints. Their contributions balanced the movement’s broader narrative, reminding us that Impressionism was not only about Paris boulevards or rural landscapes but also about private, intimate worlds. These women expanded the scope of what counted as worthy subject matter. In doing so, they gave Impressionism both nuance and inclusivity, proving that art’s revolution must include all voices. Their legacy continues, inspiring contemporary dialogues on gender and artistic visibility.

Edgar Degas was an Impressionist, yet his methods diverged from peers. While Monet and Renoir focused on fleeting light outdoors, Degas gravitated toward interiors, ballet studios, theaters, cafés. He used strong lines, unusual angles, and pastels, bringing a structural clarity absent in Monet’s fluidity. Influenced by photography and Japanese prints, his compositions often cut subjects abruptly, mirroring modern perception. Unlike plein air painters, Degas preferred controlled environments, where he could analyze movement, especially of dancers and horses. His emphasis was less on color’s vibration and more on form, rhythm, and gesture. Though critical of the “Impressionist” label, he participated in their exhibitions, expanding the movement’s scope. Degas showed that Impressionism was not monolithic, it could embrace both the atmospheric shimmer of Monet and the analytical sharpness of his own style. His difference ensured Impressionism’s richness, balancing spontaneity with discipline, fleeting light with enduring structure.

Impressionist painting unfolded in the heart of 19th century France, where the rise of the middle class, modern leisure, and redesigned Paris boulevards shaped everyday life. Artists sought not mythology but immediacy. Their subjects mirrored the pulse of a changing society, from crowded cafés to quiet gardens, from opera houses to riversides. This shift was not only stylistic but social, bringing art closer to lived experience. Landscapes captured the play of light, while urban life celebrated progress and spectacle. Impressionism’s subjects were democratic, everyday yet luminous, transforming the ordinary into timeless moments of vision and feeling.

The Impressionists broke with history painting by centering life as it unfolded. Their subjects reflected the values and rhythms of middle-class society. Instead of myth, they turned to boulevards, train stations, boating scenes, dance halls, and domestic interiors. Landscapes of the Seine and Normandy coast embodied nature’s fleeting moods, while gatherings in cafés or music halls celebrated leisure and sociability.

Typical themes included:

- Urban life: boulevards, cafés, concerts.

- Landscapes: rivers, gardens, seasonal change.

- Leisure scenes: picnics, boating, dance gatherings.

The diversity of subjects mirrored the diversity of experience in modern Paris. Painters like Renoir captured intimacy and warmth in social scenes, while Pissarro’s rural works grounded Impressionism in nature. Together, these themes gave Impressionism breadth, capturing both the spectacle of urban modernity and the quiet dignity of ordinary life. The takeaway is clear, Impressionism sought not grandeur but truth in the everyday.

The rebuilding of Paris by Baron Haussmann in the 1850s and 60s gave Impressionists a new canvas. Wide boulevards, gas lamps, and bustling crowds offered both spectacle and subject. Painters like Monet, Renoir, and Caillebotte turned their eyes to these spaces, where leisure mingled with commerce. Impressionists used quick brushstrokes to mimic movement, from carriages rolling to crowds crossing streets. Cafés became recurring motifs, places where art, politics, and pleasure converged.

Their urban vision was not merely descriptive but interpretive. Renoir’s Dance at Le Moulin de la Galette evokes joy and intimacy, while Caillebotte’s Paris Street, Rainy Day reflects alienation in modern crowds. The city was both luminous and fragmented, mirroring the new rhythms of industrial life. By painting boulevards and gatherings, Impressionists made urban modernity central to art’s vocabulary. They taught audiences to see beauty not only in landscapes but in the fleeting chaos of the metropolis.

Landscapes held a privileged place in Impressionism because they allowed direct exploration of light and atmosphere. With the invention of portable paint tubes, artists like Monet, Sisley, and Pissarro could work outdoors, observing shifts of color through the hours. The landscape became a laboratory of vision. Fields, rivers, and coastlines were not just settings but subjects alive with change.

Landscapes mattered for deeper reasons too. They connected Impressionism to tradition, echoing earlier schools like the Barbizon painters, while transforming method and mood. Monet’s Haystacks series or Rouen Cathedral studies showed how time itself could be painted. The cultural moment also shaped this focus, as industrial Paris expanded, nature became both retreat and reminder. By painting landscapes, Impressionists offered a counterpoint to urbanization, grounding modernity in seasonal cycles and elemental beauty. Their landscapes are still lessons in how fleeting light carries permanence in memory.

Impressionism did not arrive as a triumph but as a scandal. Early critics and institutions scorned its loose brushwork and modern subjects. Paintings that shimmered with vitality seemed unfinished to academic jurors. The Salon des Refusés of 1863, featuring works rejected by the official Salon, marked the start of public debate. Critics coined “Impressionism” as an insult, mocking Monet’s Impression, Sunrise. Yet the same qualities that drew ridicule would later inspire modern art. The reception of Impressionism charts a journey, from rejection to reverence, showing how innovation often travels a path of controversy before becoming canon.

The reaction was sharp and hostile. Critics derided Impressionist canvases as crude sketches, unworthy of serious art. Louis Leroy, reviewing the 1874 exhibition, mocked Monet’s Impression, Sunrise, coining “Impressionism” as an insult. Writers complained of unfinished surfaces, vulgar subjects, and lack of narrative depth. To them, the brushstrokes looked chaotic, the scenes too ordinary.

Yet even in ridicule, curiosity grew. Some saw freshness in their rebellion against academic tradition. The public crowded exhibitions, partly to mock, partly to marvel. Over time, as artists persisted, ridicule softened into respect. Figures like Émile Zola defended their innovation, framing it as truth to perception. The takeaway is striking, what begins as scandal can evolve into cultural cornerstone. Impressionism’s reception proves that art’s value is often invisible at first, requiring persistence, community, and conviction to reshape public taste.

The rejection came from the Académie des Beaux-Arts and its juried Salon, guardians of French artistic standards. These institutions prized smooth surfaces, historical grandeur, and moral storytelling. Impressionism upended these values. Quick strokes looked unfinished. Subjects like cafés, dance halls, and landscapes lacked “nobility.” Critics viewed Impressionism as amateurism disguised as rebellion.

- Visible brushstrokes clashed with academic polish.

- Modern subjects lacked grandeur compared to myth or history.

- Philosophical shift, art as perception, not narrative.

Institutions feared that accepting Impressionism meant surrendering cultural authority. By rejecting it, they preserved tradition but also fueled rebellion. The Salon des Refusés became a rallying space, where rejection turned into identity. Ironically, the same institutions later embraced Impressionism as taste evolved. Their rejection had sparked the very independence that made the movement thrive. Tradition resisted, but history sided with innovation.

Public opinion moved slowly from mockery to admiration. In the 1870s and 80s, viewers laughed at Impressionist shows, likening paintings to unfinished daubs. By the 1890s, however, collectors and dealers began to see value. Patrons like Durand-Ruel championed Impressionist art, organizing exhibitions abroad in London and New York, spreading new appreciation.

This shift happened because audiences adjusted to modernity itself. The urban crowd, once scandalized, grew familiar with trains, boulevards, and leisure, the very subjects Impressionists painted. Over time, what once shocked seemed truthful. By the early 20th century, museums began collecting their works, cementing their place in art history. The public’s change of heart reveals how culture acclimates to innovation. First outrage, then acceptance, finally reverence. Impressionism’s story is a reminder, patience and persistence can turn rejection into legacy, reshaping the very definition of art in its wake.

Impressionism did not stop in France. Its methods and spirit spread across continents, inspiring movements from Post-Impressionism to American Impressionism. Artists like Vincent van Gogh and Paul Cézanne absorbed Impressionist techniques, but redirected them toward structure, psychology, or intensity. The fascination with Japanese prints, known as Japonisme, reshaped composition with bold patterns and cropping. In the United States, painters like Childe Hassam adapted Impressionism to American light and landscapes. Global in scope, Impressionism seeded a modern language of painting. Its influence shows how one movement, born in Paris cafés and gardens, reshaped the world’s visual imagination.

Read More : Best Wall Designs That Will Inspire You to Revamp Your Home

Post-Impressionism built directly on Impressionism’s discoveries but sought new depth. Painters like Van Gogh, Cézanne, and Gauguin inherited the bright palette and loose brushwork but reimagined purpose. Van Gogh intensified color, using swirling strokes to express emotion. Cézanne structured form, turning Impressionist spontaneity into foundations for Cubism. Gauguin, meanwhile, used flat planes and symbolic color to explore spirituality.

- Van Gogh drew intensity from Impressionist light.

- Cézanne gave order to Impressionist perception.

- Gauguin extended Impressionist color into symbolism.

Post-Impressionists respected Impressionism but felt it lacked depth in structure or emotion. They carried the torch further, creating bridges to modernism. Impressionism’s impact was thus dual, both an end in itself and a starting point. Without it, modern art’s fragmentation and innovation would not have been possible. Impressionism gave future artists the courage to expand art beyond what had been seen.

The mid-19th century opening of Japan to the West flooded Europe with ukiyo-e woodblock prints, which fascinated Impressionists. Known as Japonisme, this influence reshaped composition. Prints by Hokusai and Hiroshige featured bold flat colors, asymmetry, and cropped perspectives, unlike European tradition. Impressionists like Degas and Monet eagerly absorbed these ideas.

Japanese art offered:

- Fresh ways of framing, unusual angles and cropping.

- Emphasis on flat color planes over shading.

- Everyday subjects elevated into art.

For Monet, Japanese bridges and gardens became motifs. Degas borrowed bold diagonals and off-center focus. Beyond style, Japonisme affirmed Impressionism’s rebellion against academic norms, proving art could thrive outside Europe’s canon. The encounter was both aesthetic and cultural, a dialogue between East and West. It demonstrated that modern art’s renewal often comes from cross-cultural exchange, where seeing differently transforms how we paint and perceive.

Impressionism expanded globally through exhibitions, patrons, and travel. Dealers like Durand-Ruel organized shows in London, New York, and Brussels, spreading awareness. Artists themselves traveled, Monet worked in England, while Mary Cassatt bridged France and America. By the late 19th century, Impressionism had inspired distinct schools. In the United States, Childe Hassam and John Singer Sargent adapted Impressionist light to American landscapes. In Australia, artists like Tom Roberts echoed its spontaneity.

The spread happened because Impressionism’s methods were universal. Loose brushwork, plein air practice, and attention to light could adapt to any landscape or culture. It was not only a French style but a global language. Impressionism’s diffusion proves that artistic revolutions do not stay bound by borders. They travel, absorb, and transform, leaving new accents wherever they go. The movement’s international legacy shows how modern art became truly global in its reach.

Impressionism carries a timeless resonance. Its shimmering play of light, unpolished brushwork, and focus on fleeting moments reshaped not only painting but how we perceive art itself. Today, its influence extends beyond gallery walls into digital exhibitions, fashion, and even home decor trends. It bridges 19th century radicalism with 21st century accessibility. From Claude Monet’s water lilies to Renoir’s leisure scenes, Impressionism endures because it captured life in motion, something still universal. Its legacy is not fixed in history but alive in modern creativity, preserved by museums, revived in markets, and reinterpreted for new generations.

Impressionism remains popular because it balances familiarity with innovation. At its core, it celebrated light, nature, and everyday life, subjects still relatable. Claude Monet’s Water Lilies or Renoir’s Dance at Le Moulin de la Galette resonate because they show beauty in the ordinary. Unlike academic art, which often glorified myth or religion, Impressionists embraced what viewers could recognize and feel.

Emotional accessibility: Its spontaneity allows audiences to connect without needing deep art theory.

Cultural adaptability: Impressionist ideas are echoed in photography, cinema, and digital art.

Today, Impressionist works remain bestsellers in auctions, are highlighted in virtual reality tours, and are featured in social media friendly museum experiences. The movement still whispers a simple truth, beauty is not distant, but around us, waiting in light, shadow, and fleeting detail.

Museums act as custodians of Impressionist heritage. These paintings, often layered with delicate pigments and vulnerable to light, require specialized care. Conservation teams regulate temperature, humidity, and even the intensity of gallery lighting to prevent fading. Institutions like the Musée d’Orsay or The Metropolitan Museum of Art invest in advanced preservation methods, from non invasive imaging to microclimate frames.

Beyond physical care, museums also preserve through context. They curate exhibitions that trace connections between Impressionism and modern art, weaving narratives that sustain relevance. Digitization has added another layer, high resolution scans and virtual galleries allow global audiences to engage without risking damage to originals.

Preservation is not just about storage but about keeping Impressionism alive in collective memory. Every brushstroke safeguarded, every exhibition designed, ensures that Monet’s skies and Degas’ dancers remain vivid not just for art historians, but for schoolchildren, travelers, and art lovers discovering them anew.

Read More : Complete Guide to Figure Painting and Human Representation in Art

Impressionism’s relevance lies in its philosophy, a way of seeing. It redefined art as lived experience, emphasizing perception over perfection. In today’s culture, shaped by immediacy and visual storytelling, that resonates deeply. Instagram feeds, photography, and film editing all echo Impressionist ideals of capturing moments rather than constructing staged grandeur.

Fashion designers borrow its palette of soft hues. Interior design and decor draw inspiration from its fluidity and natural light effects. Contemporary artists reinterpret Impressionist motifs through digital media, AI art, and immersive exhibitions.

Most importantly, Impressionism continues to democratize art. It insists that the fleeting glow of morning light or the bustle of a city street is worthy of representation. That ethos aligns perfectly with modern culture’s embrace of everyday beauty. Its lesson is simple but enduring, art is not only about monumental works but about the immediacy of being present, attentive, alive.