A rug is never just a rug. It is a story laid flat. It holds memory, belief, habit, fear, hope, weather, soil, prayer, loss, and survival. Long before rugs became decor, they were language. They were not made to match sofas. They were made to hold worlds.

In many old cultures, people did not write. They wove. What they could not record with ink, they recorded with wool. What they could not say aloud, they knotted into shape. Every line had meaning. Every shape had purpose. Every color carried a reason.

Today we often see rugs as pattern and texture. We talk about style, tone, vibe. We forget that most of these forms were never made for beauty alone. They were made to protect. To bless. To warn. To remember. To pass on knowledge.

This is why traditional rug patterns feel so alive even now. They were never meant to be silent. This piece looks closely at how these patterns speak. Not in mystery language. In human language. Simple. Grounded. Real.

We begin with one of the oldest and most powerful symbols in woven history.

The medallion is the heart of many traditional rugs. It sits at the center, calm and steady, like an eye that sees everything. In old weaving cultures, the center was not a design choice. It was a worldview.

Many early societies believed that life had a center. A point where heaven, earth, past, and future met. This point was not physical. It was spiritual. The medallion became the shape of that idea.

When a weaver placed a medallion in the middle of a rug, they were not decorating. They were mapping meaning.

In Persian traditions, the medallion often stood for the universe. The outer borders showed the known world. The center showed the unseen order that held it all together. It was the idea that chaos had a core. That life had structure even when it felt random.

In some regions, the medallion was linked to the sun. The giver of life. The keeper of time. The witness of seasons. This is why many medallions glow with strong reds, golds, deep blues. They were not chosen to match furniture. They were chosen to echo the sky.

In nomadic cultures, the medallion sometimes stood for the self. A reminder that the person standing on the rug was part of something larger. You were not alone. You were placed inside a cosmic map.

This is why medallions are often symmetrical. Symmetry was not about neatness. It was about balance. It said that life must return to harmony. Even after loss. Even after war. Even after drought.

Some medallions look like flowers. Some look like stars. Some look like shields. Each shape carried local meaning. A floral medallion might speak of fertility and land. A star shaped one might speak of guidance and fate. A shield form might speak of protection.

When these rugs were placed in homes, tents, or prayer spaces, people were not just walking on them. They were stepping into a symbol of order.

Even today, medallion rugs feel grounding. People say they bring calm. They say they anchor a room. They do not always know why.

The body remembers what the mind has forgotten.

Read More : Rug Care & Maintenance- How to Make Rugs Last for Decades

The Tree of Life is one of the oldest symbols known to humans. It appears in stories from India, Persia, Central Asia, Africa, and Europe. It is not tied to one religion. It belongs to human memory.

In rugs, the Tree of Life is rarely drawn as a realistic tree. It is stylized. Abstracted. Simplified. But its message remains strong.

It stands for connection.

Roots go down. Branches go up. The trunk stands between. This made the tree the perfect symbol for the link between earth, people, and sky.

In rug traditions, the Tree of Life often represented the soul. Its roots showed ancestry. Its trunk showed present life. Its branches showed future generations. It said that a person was not a single moment. They were a chain.

In some Islamic weaving traditions, the Tree of Life also symbolized eternal life. Gardens of paradise were often imagined as places of shade, water, fruit, and endless growth. Rugs with tree motifs became small portable gardens.

In nomadic cultures, where land could be harsh and uncertain, the tree was a dream. Many of these people lived in areas where large trees were rare. So the image of a tall, full, living tree became a symbol of abundance.

This is why Tree of Life rugs often use greens, blues, and soft warm tones. They were not copying nature. They were imagining it.

Some Tree of Life rugs show birds in the branches. These birds often symbolized souls. Messages. Freedom. Transition between worlds.

Some show flowers growing from the trunk. These stood for rebirth. Healing. New beginnings.

The shape itself was also important. The vertical rise of the tree helped guide the eye upward. This upward movement reminded people that life was not only about survival. It was also about meaning.

Many of these rugs were used in prayer spaces. Sitting on them meant sitting beneath a symbol of divine order. It was a way of placing oneself inside a story of purpose.

Even now, when people see Tree of Life rugs, they often describe them as peaceful. Hopeful. Alive.

That is not coincidence. That is memory speaking.

The Boteh is often called paisley today. But its roots go much deeper than fashion.

The Boteh shape looks like a droplet. Or a flame. Or a bent leaf. Or a seed. Its power comes from this ambiguity. It can mean many things at once.

In Persian traditions, the Boteh was linked to growth and eternity. Its curved shape suggested movement. Not stillness. It was a symbol of life unfolding.

Some scholars believe it began as a stylized cypress tree. The cypress was sacred in many cultures. It stood for endurance. It stayed green even in harsh conditions. This made it a natural symbol of the soul.

In other traditions, the Boteh was seen as a flame. Fire was sacred. It purified. It transformed. It kept people warm. A flame also bends but does not break. This gave the Boteh its association with resilience.

In India, where the paisley later became popular, the shape was tied to fertility and prosperity. It was linked to mango seeds. Growth. Sweetness. Renewal.

When this symbol traveled through trade routes, its meaning shifted but never disappeared. Each culture layered new stories onto it.

In rugs, the Boteh was often repeated many times. This repetition was not decorative. It was philosophical. It said that life was made of cycles. Birth. Death. Return.

Small Botehs could mean seeds. Potential. Large ones could mean protection and power.

Their curved tip often pointed inward. This was thought to help guide energy into the space. A way of keeping good forces close.

When you look at a paisley pattern today, you may think of fashion. Scarves. Prints. Luxury.

But its true origin was much quieter. It was a symbol of survival. Of softness that endures.

It is a reminder that beauty does not have to shout. Sometimes it bends.

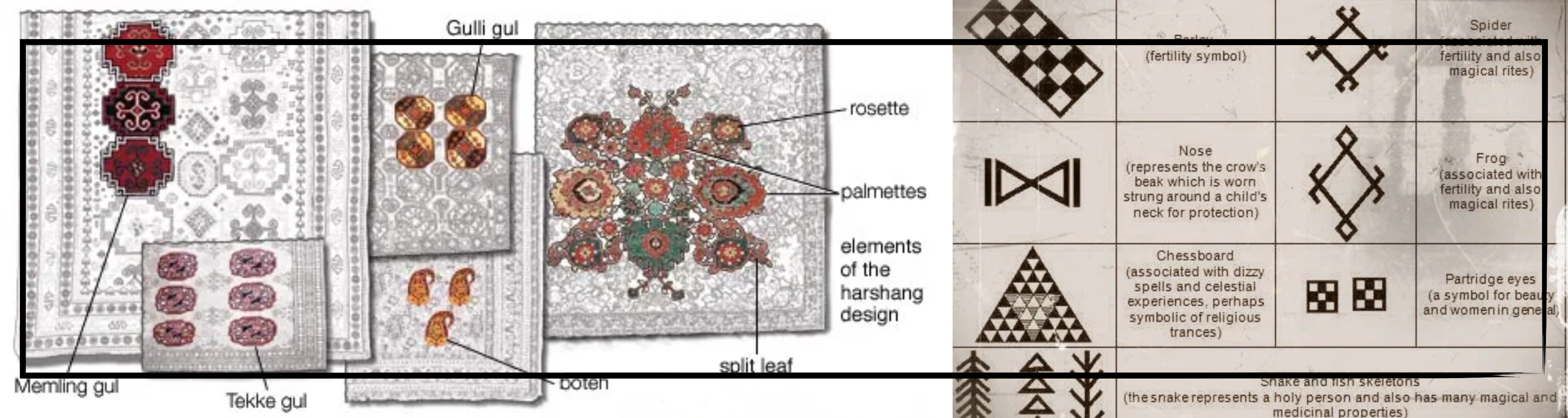

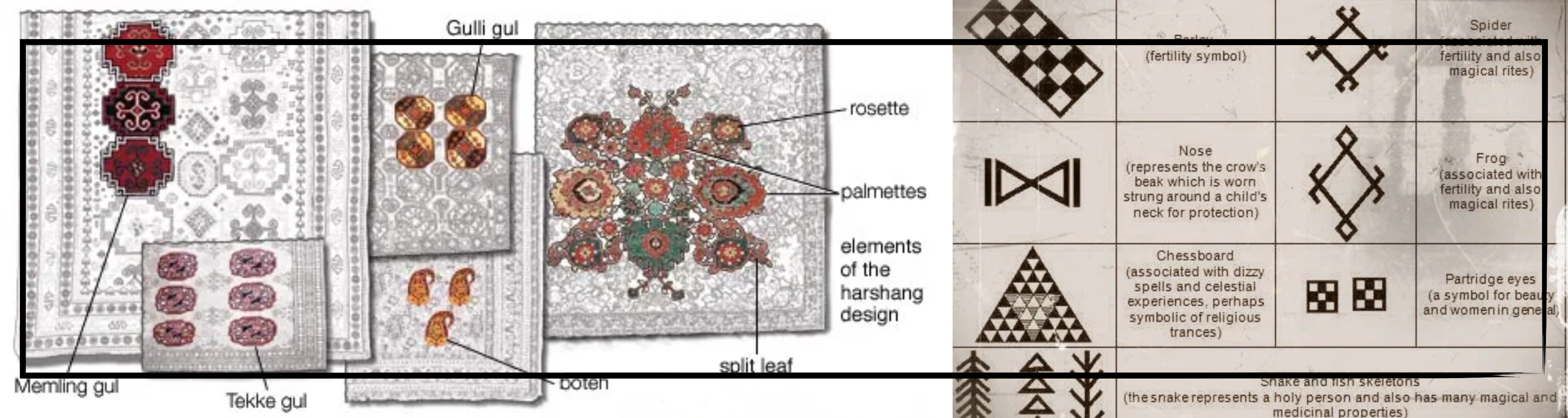

Many tribal rugs are filled with sharp lines, angles, diamonds, hooks, and steps. To modern eyes, they can feel abstract. But to the people who made them, they were sentences.

These shapes formed a visual language.

In societies without writing systems, weaving became a way to record experience. Each motif could stand for an event, a warning, a prayer, or a memory.

A diamond might mean fertility or the female form. A hooked shape might mean protection against evil. A zigzag might represent water, lightning, or life energy.

Triangles often symbolized mountains. Stability. Shelter. Strength.

Stepped shapes sometimes represented journeys. Both physical and spiritual.

Repetition in tribal rugs was not about symmetry alone. It was about emphasis. Just like repeating a word makes it stronger, repeating a motif made its meaning louder.

Colors also carried meaning. Red could stand for blood, life, and courage. Blue often stood for sky, fate, or divine order. Black could mean soil, death, or protection. White could mean purity or mourning depending on the region.

None of these meanings were random.

Weavers learned this language from elders. From mothers. From watching. From stories told by firelight.

A rug could show the story of a marriage. A safe crossing. A drought. A victory. A lost child.

It could also act as a shield. Many rugs were believed to trap harmful forces within their patterns. The complexity confused negative spirits. The borders kept them contained.

This is why tribal rugs often feel intense. They are not quiet objects. They are loud with memory.

When these rugs entered global markets, much of this language was erased. They became ethnic patterns or boho designs.

But the grammar is still there.

The shapes are still speaking.

To understand rugs is to understand people.

Traditional rug patterns are not aesthetic trends. They are survival tools. They are memory systems. They are emotional maps.

When we lose their meanings, we lose a way of reading human history.

A rug is one of the few objects that touches daily life while carrying deep symbolism. You walk on it. You sit on it. You pray on it. You sleep on it. It becomes part of the body.

This closeness matters.

It means these patterns were never meant to be distant art. They were meant to be lived with.

This is why rug symbolism feels different from museum symbolism. It is intimate. It is warm. It is worn.

Understanding these symbols teaches cultural humility. It shows us that people across the world asked the same questions. Where do we come from. Why do we suffer. What protects us. What lasts.

They answered with wool.

In a world that moves fast, these rugs remind us that meaning can be slow. That stories can be knotted into time.

They ask us to look longer.

To feel more.

To remember that design once had soul.

Symbols travel, but they never remain unchanged. They move the way stories move, shaped by land, climate, belief, and survival. Each region that adopted these motifs added its own accent, its own emotional weight, its own interpretation of what mattered most. This is why the same medallion can look calm in one place and fierce in another, why the same geometric line can feel soft in one rug and sharp in the next. These are not inconsistencies. They are cultural fingerprints.

In Anatolia, many medallions became angular rather than curved. Lines hardened into steps and edges became more pronounced. This was not a matter of taste alone. It reflected the terrain itself, rocky and unyielding, and the reality of life there, which demanded endurance. The forms mirrored the environment. In Caucasian rugs, patterns grew bold and colors intensified. Reds burned brighter and blues deepened, not simply for beauty but as expressions of resilience. These regions often lay along routes of conflict and trade, and their rugs absorbed that tension. Borders became heavier, protective motifs more frequent, and the edges more deliberate.

Central Asian tribal rugs, especially those of Turkmen origin, compressed meaning into dense arrangements. Space was rarely left empty. This mirrored nomadic life, where every possession had to justify its presence. Nothing could be wasted. In contrast, Indian weaving traditions allowed more openness. Florals expanded, curves softened, and movement became fluid. These designs reflected a worldview tied to abundance, ritual, and seasonal rhythm rather than survival through scarcity. No matter the geography, one truth remained constant. Rugs were never neutral. They were expressions of how people understood existence.

A rug does not merely decorate a room. It shapes how a space feels, and this is not metaphorical language. It is sensory reality. The human brain responds instinctively to pattern, symmetry, repetition, and rhythm. These are not learned reactions. They are wired into perception.

Early weavers may not have known neuroscience, but they understood the body. They knew what brought calm, what created safety, and what eased the mind after long days of uncertainty. A central medallion gave the eye a place to rest, reducing visual strain. Repeating motifs created rhythm, and rhythm steadied the nervous system. Borders defined safety by marking where a space began and ended. Vertical motifs such as trees or columns guided attention upward, subtly lifting mood, while horizontal bands grounded the body.

These effects were not aesthetic accidents. They came from lived experience. People wove what made them feel protected, hopeful, and emotionally held. This is why certain rugs still make people feel at home even when they cannot explain why. Memory does not always speak in words. Sometimes it speaks in pattern.

Traditional rugs were never meant to be admired from a distance. They were meant to be lived on. They kept bodies warm, blocked wind, created privacy, marked sacred ground, and softened hard surfaces. Beauty was not the primary goal. Meaning was.

Over time, as trade routes expanded, these rugs traveled far from their origins. People who did not understand the original symbolic language still felt their presence. They sensed intention even if they could not decode it. Slowly, rugs shifted from necessities to valued objects. Collectors sought them, palaces displayed them, and markets categorized them.

Something important was gained through this process. Preservation. But something was also lost. Literacy. Patterns were admired without being understood. This is similar to ancient scripts that are now visually appreciated but no longer read. Learning rug symbolism is a form of cultural reading. It restores voice to what has become silent.

Read More : Rug Care & Maintenance- How to Make Rugs Last for Decades

Today, rugs often sit inside minimalist spaces. White walls, clean lines, quiet furniture. Ancient symbols now live inside modern rooms, creating a subtle tension between worlds. A motif once used for protection now rests beneath a coffee table. A pattern tied to prayer lies beside a bookshelf.

This is not a mistake. It is evolution. Cultures shift, and meanings travel. But when symbolism is erased, something becomes thin. Understanding these patterns does not require using them traditionally. It requires relating to them consciously. A medallion becomes grounding rather than decorative. A Tree of Life becomes continuity rather than ornament. A Boteh becomes resilience rather than print. Geometric motifs become strength rather than style.

The rug stops being passive. It becomes a participant in the space.

Across cultures, humans hide stories in objects. Pots, clothing, walls, jewelry, songs, and tools all carry layers of meaning. This happens because people fear forgetting. Memory fades. Wool lasts.

Rugs functioned as portable libraries. They carried identity. They traveled with families. They were passed from generation to generation. A grandmother could explain a motif to a child, and the child would remember that story every time they stepped onto it. In this way, memory became physical.

This is why the decline of traditional crafts is more than an economic loss. It is a cultural erasure. When weaving traditions disappear, a language disappears. Not a spoken one, but a visual one. Learning to read this language allows us to see cultures not as decoration, but as systems of knowledge.

Decoration exists on the surface. Meaning lives in depth. Modern design often asks how something looks. Traditional craft asked what something does.

Does it protect. Does it bless. Does it guide. Does it remember.

This is why old rugs feel heavy with presence. They were never meant to be empty. They were meant to hold life. Even wear marks carried stories. A faded area showed where people sat, where they prayed, where they gathered. Wear became biography. This is why old rugs feel alive. They have lived.

Modern life teaches people to glance, scroll, and skim. Traditional symbols ask for something else. They ask for slowness. They ask for attention.

This is not nostalgia. It is skill. Learning to read visual language sharpens perception. You start noticing intention. You stop assuming randomness. You begin to ask what a thing is trying to say.

This way of seeing does not stop at rugs. It extends to architecture, clothing, ritual, and art. Once you realize that humans encode meaning everywhere, the world becomes less flat and more layered.

With understanding comes a quiet question. What does it mean to walk on sacred symbols. What does it mean to place prayer patterns beneath furniture.

There is no single answer. Cultures change. But awareness changes relationship. When you know a symbol stands for protection, you treat it differently. When you know a motif is tied to mourning, you approach it with more care.

Respect begins with understanding. Understanding begins with listening.

Rugs have been speaking for centuries. We simply forgot how to hear.

Traditional rugs are not relics. They are living archives. They carry philosophy without words, emotion without sentences, and history without books. They remind us that humans have always been thinkers, storytellers, and designers of meaning. They show that art was once inseparable from daily life.

Read More. : Rug Size & Placement Guide- Perfect Fit for Every Room

Not distant. Not elite. Not abstract.

It was underfoot.

When we learn to read these patterns again, we do not only gain cultural knowledge. We gain a different way of seeing. One that values continuity. One that recognizes intention. One that understands that beauty was never just about appearance.

It was about survival with meaning.

A rug is never just a rug. It is a map of how someone once understood the world. And if we learn to read it, we might understand ourselves a little better too.