Samyoga Sringara Rajasthani Bundi School Krishna and Radha Framed Paper Print with Po...

- ₹ 4,500.00

-

Only 1 left

The Month of Asadh Kangra School Monsoon Scene Framed Paper Print with Poem by Kalida...

- ₹ 4,500.00

-

Only 1 left

Radha and Krishna in the Forest Kangra School Framed Paper Print with Poem by Chandi ...

- ₹ 4,500.00

-

Only 1 left

Framed Paper Print of Seated Figure in Reflective Pose with Soft Impressionistic Brus...

- ₹ 5,200.00

-

Only 1 left

Nathdwara Shrinathji Din ke Darshan Traditional Monochrome Paper Painting Framed

- ₹ 4,500.00

-

Only 1 left

The Charm of Old Prints and Paintings

Old prints and antique paintings are time-stitched chronicles, crafted not just to decorate walls, but to preserve epochs. They hold within their surfaces the weight of civilization, nostalgia, and mastery of forgotten techniques. Often made using tools and pigments no longer in use, they possess an aura—cracked varnish, softened outlines, and fading ink that echo human transience. Each work speaks to a moment suspended, with tactility and tone embedded into its canvas or paper. Whether etched with burins or brushed in tempera, these pieces are not static—rather, they breathe with the rhythm of history. They remind us that before the digital eye, the artist’s hand was the ultimate recorder.

What Is An Old Print Or Painting?

An old print or painting is a tangible manifestation of artistic legacy, often created before the 20th century, using traditional methods like copperplate engraving, woodcut, mezzotint, or oil on linen canvas. These are not merely images but engraved memories—etchings of empires, lithographs of revolutions, and portraits frozen in oil with an almost whispering realism. Prints are typically mechanically reproduced but individually inked and pressed by hand, making each impression slightly unique. Antique paintings, on the other hand, showcase single-origin brushwork layered with gesso, glaze, and underdrawings. Patinas, craquelure, foxing—such terms define their aging textures. They are timekeepers, wrapped in frames as if housed in relics. In essence, they serve as aesthetic time capsules: pigment, pressure, and paper or canvas united in silent dialogue with the viewer.

What Do Old Prints And Paintings Aim To Capture Or Convey?

Old prints and paintings aim to do more than depict—they immortalize. Be it a pastoral landscape, a mythological drama, or a noble’s finely pleated attire, these works are imbued with intention. Through chiaroscuro and cross-hatching, they reveal not just the scene, but the societal temperament of their time. Painters and printmakers—often court chroniclers, silent commentators, or radical dreamers—used their mediums to freeze ideologies, political climates, or quiet domesticities. Light and shadow converse across paper or canvas, symbolizing divine grace, social hierarchy, or melancholia. Many works aimed to either instruct, inspire awe, or provoke discourse. Through composition, iconography, and material decay, these pieces invite viewers to witness not just what was seen—but what was felt. Each stroke, each press, is an act of translation—from thought to pigment, from moment to eternity.

What Are The Different Types Of Old Prints And Paintings (E.G., Lithographs, Etchings, Oil Paintings)?

Old prints and paintings span a rich spectrum of techniques, each with its own syntax of style and surface. Etchings involve acid-bitten lines on a metal plate, offering a loose, calligraphic quality—Rembrandt made this process deeply emotive. Engravings, by contrast, use a burin to incise clean, precise lines, often seen in early scientific illustrations or portraits. Lithographs are drawn with greasy crayons on stone, allowing for tonal variation and artistic spontaneity, favored by artists like Daumier. Woodcuts and linocuts, bold and graphic, were often used in religious texts or social commentary. Oil paintings, rich in impasto and depth, allowed Renaissance and Baroque artists to sculpt light and texture. Tempera, an earlier medium, yielded crisp, matte finishes, often used in iconography. Each method tells a different story—not just in subject, but in feel. Their surfaces hold both deliberate marks and accidental grace: fingerprints, smudges, age spots—details that time alone can paint.

Techniques & Tools of Old Prints and Paintings

The craftsmanship of old prints and paintings resides in a harmony of medium, method, and moment. Artists didn’t just create—they etched, layered, and illuminated their intentions. Whether through woodcut, etching, mezzotint, or aquatint, each method breathed its own rhythm into the artwork. The tools—burins, styluses, and ink rollers—were extensions of thought, moving across handmade rag paper or primed canvas. Pigments were natural—ground stones, minerals, and organic dyes, bound in oil or gum arabic. Every mark was intentional, every stroke layered with purpose. These weren’t just visuals; they were relics of time, processes, and patience, echoing stories in texture and tone.

How Are Old Prints And Paintings Traditionally Created?

Old prints and paintings were created through techniques that demanded precision, patience, and deep knowledge of materials. Printmaking methods such as woodcut, engraving, etching, and lithography were employed to transfer inked designs onto paper. Each began with a carefully prepared matrix—woodblock or metal plate—etched with a stylus or burin. Ink would be applied, wiped, and then pressed onto paper using a printing press. Paintings, on the other hand, followed a more layered process. Artists would stretch canvas or prepare wood panels, apply gesso, sketch outlines with charcoal, and layer egg tempera, oil, or casein paints, allowing each layer to dry before proceeding. Brushwork and glaze defined depth, while gold leaf or pigment detailing brought luminosity. These works were not spontaneous; they were meditative, ceremonial, deliberate acts of creation. Every element—composition, medium, tool—was part of an inherited vocabulary of art, passed down like silent hymns through the hands of generations.

What Materials Were Traditionally Used (Papers, Inks, Canvas, Pigments)?

The materials of traditional art were sacred choices, echoing culture, geography, and craftsmanship. Handmade rag paper, often cotton-based, offered durability and a receptive surface for inks and washes in printmaking. Vellum or parchment was also used for illuminated manuscripts and miniature paintings. For paintings, linen or hemp canvas, primed with rabbit-skin glue and gesso, provided the ideal surface. Wooden panels—often oak or poplar—were also favored in early Renaissance works. Inks were handmade using lampblack, iron gall, or sienna, while paints drew color from ground lapis lazuli, malachite, ochre, and vermilion, bound in egg yolk for tempera or linseed oil for oil painting. Natural resins, varnishes, and gold leaf completed the piece, adding a celestial glow. These materials weren’t arbitrary—they were alchemical. Each held regional significance, economic value, and spiritual meaning. In their very grain and hue, they preserved the silent dialogues between artist, earth, and eternity.

How Do Artists Choose The Right Technique Or Medium For Historical Pieces?

Choosing a technique or medium in historical artwork was both an intuitive and technical decision, shaped by purpose, patron, and period. Artists considered durability, luminosity, and the nature of narrative. If the subject required sacred depth—like a religious icon—egg tempera on wood was preferred for its brilliance and control. For portraits and atmospheric effects, oil on canvas offered flexibility and a longer drying time, allowing subtle glazes and corrections. In printmaking, etching provided delicate linework, while woodcut conveyed bold, graphic storytelling. The intended audience also influenced choices; devotional books were illuminated on vellum, while public messages often used reproducible engravings. Local materials, training under specific schools (Florentine, Dutch, Mughal), and access to specific resources—lapis lazuli, gold leaf, or particular woods—further guided medium selection. Technique wasn’t merely functional—it was expressive. Artists matched subject to substance, form to feeling, allowing the medium to amplify the soul of the story being told.

Purchase & Options of Old Prints and Paintings

Old prints and paintings aren’t just art pieces; they are echoes of epochs, whispers of craft. Purchasing them isn’t about ownership—it’s about communion. Whether it’s a mezzotint from the Victorian age or a hand-coloured lithograph from colonial India, these visuals carry texture not just in pigment but in time. Each brushstroke or engraved line holds the patina of intention. The choice to collect such works is rooted in taste, heritage, and an innate longing to preserve visual storytelling. From sepia-toned aquatints to vivid gouaches, the marketplace teems with forgotten genius. But one must look beyond commerce—into character, signature, and source.

Where Can You Buy Authentic Old Prints And Paintings?

Authenticity begins with provenance. Reputed auction houses like Sotheby’s or Christie’s often showcase curated collections of old master prints, European etchings, or Raj-era watercolours with traceable documentation. Galleries specializing in period-specific or regional art—like those dealing in Mughal miniature reprints or Edo-period Japanese woodcuts—provide legitimacy through scholarly curation. Art fairs and exhibitions may offer access to both dealers and conservators, allowing tactile engagement and background inquiry. Online portals such as Artnet or 1stDibs are increasingly reliable, but only if the seller provides clear proof of age, medium (etching, chromolithograph, hand-pulled print), and condition. Always ask about restoration, archival backing, and signature validation. In India, old bazaars and heritage shops in Jaipur or Kolkata offer hidden gems, but demand the collector’s eye. Authenticity, ultimately, lies in detailed observation and educated intuition—examining paper texture, ageing marks, and even watermark impressions.

Comparison of Old Prints

Old prints are more than just images—they are tactile impressions of history etched in wood, copper, or stone. Each line in an etching, each texture in a mezzotint, carries the residue of time, technique, and intention. Unlike digital prints, old prints exhibit plate marks, faded inks, and paper grain—all signs of human craftsmanship and age. The chiaroscuro, the hatching, and the bleeding pigments together form a textured language lost in modern replication. These prints feel lived-in, intimate, and quietly radiant. They are not just visuals; they are artefacts of method—engraved whispers from centuries past.

Old Prints Vs Modern Reproductions: What’s The Difference?

Old prints are created through hands-on printmaking methods like etching, aquatint, or lithography—where the artist physically interacts with a plate or stone. These works carry idiosyncrasies: a burin’s misstep, the uneven inking, the texture of laid paper. Modern reproductions, in contrast, are usually digital replications—flat, uniform, and lacking the tactile history of the original. Reproductions mimic, but they do not hold the weight of age or process. There’s no bite of ink into paper, no embossment from the press. While reproductions may serve decorative or educational purposes, they exist outside the aura of authenticity. In comparison, old prints hold provenance, an artistic fingerprint. Their value lies not just in the image but in the medium's honest limitations—its decay, its errors, its human imprint.

Creative Use & Aesthetics of Old Prints

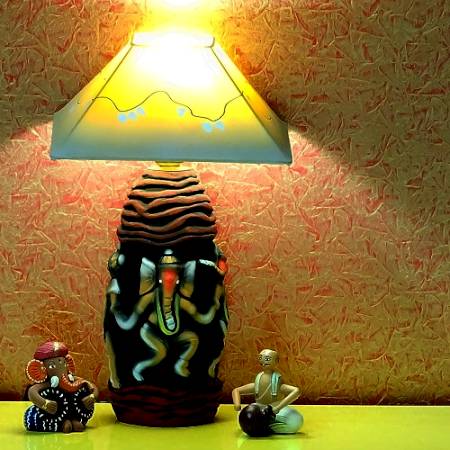

Old prints possess a melancholic beauty—delicate, faded, but deeply resonant. Their subdued palettes, deliberate compositions, and rhythmic lines create a poetic stillness that modern art often bypasses. They offer an analogue richness, a visual tactility that harmonizes with both vintage and contemporary aesthetics. Framing an old lithograph beside raw-textured fabrics or brass décor objects brings a balanced depth. These prints also act as visual punctuation—inviting pause, memory, and reflection. A well-placed old botanical engraving, with foxed edges and off-white paper, does more than decorate; it narrates. It brings into space the language of restraint, of curated quiet.

How Can Old Prints And Paintings Be Used Creatively In Decor Or Art Projects?

Old prints can be recontextualized as layered narratives in modern interiors. In gallery walls, a juxtaposition of old architectural etchings with abstract canvases creates dynamic dialogues. Artists often use fragments of vintage prints in collage—reconfiguring old engravings into new compositions, turning allegorical figures into surreal montages. In décor, try reverse-framing to expose the backing inscriptions, signatures, or watermarks—celebrating the full anatomy of the artwork. Designers also use scanned sections of old prints in textile design, wallpaper patterns, or stationery aesthetics, adding classical elegance to functional design. Whether arranged in a grid, asymmetrical cluster, or solitary highlight, old prints offer emotional and visual gravity. Their presence in a space feels like an echo—subtle, historical, but always intentional.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What Are Old Prints And Paintings Typically Used For?

Old prints and paintings serve as windows to lost epochs, suspended in pigment and pressed ink. Beyond aesthetics, they often function as tactile memory—a visual document of civilization’s evolving form, spirit, and taste. In homes, they transform walls into quiet storytellers, while in museums they hold the weight of context and lineage. Whether etched by copperplate or stroked with tempera, such works invite contemplation, elevate spatial ambience, and preserve artistic dialects of their time. Often used in curatorial collections, heritage restoration, or thematic décor, they are not merely décor—they are dialogues between the viewer and time itself. The patina, faded gilt, and matte monochrome act as tone-setters for interiors seeking depth. Fragments of narrative, held in these artefacts, offer cultural permanence in increasingly transient spaces, anchoring the eye and soul.

What Surface Or Mounting Is Ideal For Framing Antique Artworks?

Archival-grade backings and acid-free mat boards are essential when mounting antique prints or paintings, especially those on delicate rice paper, parchment, or hand-laid rag. Canvas-based oils require stretcher bars and protective glazing only if in unstable climates. Avoid direct adhesion; instead, opt for T-hinge mounting or corner pockets for prints. Museum glass or UV-filtering acrylic protects against harmful rays without compromising clarity. For works with deckled edges, float mounting allows their handmade nature to breathe. The frame must not overpower the piece; giltwood, distressed walnut, or ebonised mahogany often pair well with classical tones. Linen or silk-wrapped mats amplify the archival aura. Avoid adhesives touching the artwork—preservation lies in invisibility. The mounting isn’t just a display method; it becomes an extension of the piece’s provenance and survival.

Can Antique Paintings Be Preserved Without Professional Help?

Preserving antique artworks without professional intervention is possible, but requires sensitivity, patience, and knowledge of the medium. Avoid storing in areas prone to humidity shifts—attics and basements are enemies to varnish and paper fibers. Use gloves to prevent oil transfer; even one fingerprint may etch itself over time. Place desiccants nearby but never touching the artwork. If it’s a canvas, ensure it’s taut but not overstretched. Light exposure must be minimal; warm LEDs are safer than incandescent bulbs. Use archival sleeves or acid-free portfolios for unframed works. Clean only the frame—never attempt surface cleaning without knowing the binder (egg tempera reacts differently than oil). Dust gently using a soft natural-bristle brush. While professionals have tools like consolidation agents or infill pigments, a careful guardian can still extend an antique piece’s life through mindfulness and respect.

Are Old Prints And Paintings Durable Or Fragile Over Time?

Their durability is paradoxical—resilient yet vulnerable. Old prints etched on rag paper or vellum may survive centuries, but sunlight or acidic exposure can bleach their soul. Paintings, especially those layered in oil, often develop craquelure—a spiderweb of age and atmosphere. However, this is not a flaw but a fingerprint of survival. The fragility lies not in the materials alone, but in handling, storage, and the environment. Watercolours, with their light-sensitive pigments, can fade silently; while wood panels may warp, canvas may slacken. A sudden temperature swing can shift layers, causing flaking. These artefacts aren’t fragile in spirit—they have travelled generations—but their surfaces require reverence. Their survival is a silent agreement between time and care.

What Technique Gives The Richest Textures Or Deepest Contrast In Old Art?

Chiaroscuro in oil, mezzotint in prints, and impasto in both mediums offer unmatched depth. Chiaroscuro manipulates light and shadow, creating dimension that breathes. Caravaggio’s darkness wasn’t void—it was volume. Mezzotint, with its velvety gradients, allowed early printmakers to render tonality akin to painting, while aquatint brought a powdery softness. In tempera, cross-hatching adds tactile rhythm; in etching, burin pressure shapes the psyche of a line. Impasto—the physicality of raised pigment—lets viewers not just see but feel emotion. These techniques weren’t decorative choices; they were psychological tools, used to pierce and cradle human emotion. Texture isn’t embellishment—it is voice.

Are Traditional Techniques Common Across Cultures?

Yes, but their manifestations are varied by geography and spirit. From Mughal miniature wash to Japanese woodblock (ukiyo-e), from European grisaille to Persian tazhib, the core remains—layering, repetition, symmetry, and storytelling through brush or burin. Sfumato finds its echo in Indian Rajput paintings' feathered lines. Gilding threads the icons of Byzantium and Tibetan thangkas alike. What unites them is the devotion to detail and the dialogue between pigment and philosophy. Art across cultures echoes the same heartbeat—only in different dialects of technique. Materials shift—silk, papyrus, parchment, bark—but the hands behind them all seek permanence through precision. This cross-cultural echo forms the scaffolding of global visual history.

What Is The Cultural And Historical Significance Of Antique Paintings?

Antique paintings are memory capsules—emblems of an era’s ethos, ideology, and identity. A Dutch still life tells of colonial trade routes; a miniature portrait whispers aristocratic legacy. They aren't merely expressions—they’re evidence. In revolutions, they carried propaganda; in peace, they were contemplations. Every crack, pigment, and inscription becomes a footnote to history. They hold the psyche of their age—the theological, political, romantic tensions of that time. From Mughal miniatures chronicling courtly love to colonial engravings mapping conquests, art becomes a soft form of documentation, often more revealing than text. Antique paintings embody not just beauty, but chronology.

How Can One Maintain Or Restore Old Prints And Paintings?

Maintenance begins with climate control—stable humidity (around 50%) and temperature (18–22°C). Framing should be archival, glazing UV-protective. Rotate displays to reduce light exposure. Restoration, if needed, should respect the original hand—overpainting is erasure. Techniques like inpainting (filling losses using reversible materials) and lining (reinforcing aged canvas) demand trained hands. If varnish yellows, it may be removed chemically, but only by professionals. Dust gently, store vertically, and avoid contact with acidic materials. Label and log conditions annually. Never attempt patching or glue on your own; memory, once disrupted, may be unrecoverable. Restoration isn’t resurrection—it’s respectful revival.

How Do Technique And Texture Set The Mood In Antique Works?

Technique and texture are not decorative—they're emotional dialects. A thin glaze in oil evokes introspection, while a heavy impasto shouts turmoil. A burnished mezzotint whispers melancholia; a coarse drypoint scratches tension. Egg tempera’s matte surface suggests calm order, whereas gouache's density vibrates urgency. The linework’s rhythm—whether hurried or meditative—sets psychological pacing. Technique becomes narrative; texture, its tone. These choices define emotional access points for the viewer. A surface isn’t neutral—it speaks. In antique works, the very brushstroke becomes mood; a single sgraffito line can feel like a rupture in memory. Every grain and groove carries affect.

How Can Old Prints Be Matched With Room Decor Or Wall Palettes?

Old prints don’t need to blend—they need to anchor. Sepia-toned engravings sit well against dusty pastels or moody emeralds. Monochrome etchings find contrast in burnt sienna or indigo walls. Gold-framed Romantic pieces glow on charcoal or muted taupe. Let the artwork dictate the room’s tempo—pull out a shade from its shadows, echo a motif in upholstery. Grouping by theme—botanical, architectural, mythological—creates curatorial cohesion. Use negative space generously; antique prints benefit from breathing room. Layer with textiles or rustic woods for synergy. When done right, old prints don't merely decorate—they orchestrate a room’s atmosphere.

Can Old Prints And Paintings Be Given As Gifts?

Absolutely, though the gift is more than aesthetic—it is a gesture of timelessness. Gifting an antique artwork is akin to gifting a fragment of history. It requires thought: knowing the recipient’s tastes, choosing works with narrative or symbolism they relate to. A woodcut of a cityscape for a traveler, a floral engraving for a botanist, a religious icon for a spiritual seeker. Accompany it with a story—about the artist, the era, or even the technique. Framed correctly, it becomes an heirloom in waiting. This isn’t casual décor; it’s an artifact curated for meaning.

What Are Some Creative Ways To Display Or Personalize Antique Art?

Gallery walls with eclectic frames can dramatize intimacy. Floating mounts showcase deckled edges, while backlit alcoves transform sacred iconography into shrine-like experiences. Pair an old print with handwritten poetry, pressed botanicals, or textile swatches from the era to layer narrative. Display under domed glass or in shadow boxes for dimensionality. Grouping by paper tone, not theme, creates tonal rhythm. Use easels for rotating pieces or hang prints over reclaimed wood boards for rustic contrast. Let each piece converse with surroundings—position them where light glances gently or near reflective surfaces to echo time. Display becomes storytelling, not just arrangement.