Encaustic painting, an ancient art reborn in modern hands, blends fire, wax, and pigment into a tactile symphony of memory and emotion. Each layer—brushed, fused, and reworked—reveals not just color, but time itself, suspended in translucent depth. This medium invites both control and surrender, where imperfections breathe life and warmth lingers in texture. It’s more than technique—it’s ritual, a slow-burning dialogue between the artist and the elements. In encaustic, the surface holds secrets: scars, glows, whispers. To paint with wax is to preserve a fleeting moment, not in silence, but in the hush between heat and stillness.

Encaustic painting, at its core, is where fire meets color. Rooted in ancient technique and timeless patience, it’s a method where pigments are mixed with hot beeswax and then applied to a surface—typically wood. Each layer is reheated and fused, building depth, texture, and luminosity in a way that’s tactile and hypnotic. There’s something meditative in watching wax melt into itself, preserving both the moment and the emotion. It isn’t just a painting; it’s a sediment of heat, time, and soul. With each stroke, the artist isn’t merely applying pigment—they’re sealing fragments of thought, encapsulating feeling, and letting permanence breathe in a world otherwise too transient. This technique invites not just the eye, but the hand and heart to lean closer. It’s where art doesn’t just speak—it pulses.

The word “encaustic” finds its roots in the Greek word enkaustikos, meaning “to burn in.” This etymology isn’t just a linguistic nod—it’s a revelation of method. Fire is not merely a tool in encaustic painting; it's the soul of it. The process involves applying molten wax and then using heat—often from a blowtorch or heated iron—to fuse layers together. This "burning in" binds the pigment to the surface, not with time or air, but with flame. The name feels ancient and alive, almost ritualistic. There’s something inherently alchemical about it, evoking a practice that predates modernity, where craftsmanship met ceremony. The term anchors the medium in a lineage that stretches back to Greek and Roman times, whispering of mariners’ portraits, mummy panels, and timeless seascapes. To call it “encaustic” is to honor the heat, the hand, and the history embedded in every luminous layer.

Read More : Shekhawati: Land of Legacy and Frescoes

Encaustic painting, rooted in ancient Greece around the 5th century BCE, began as a technique to seal ship hulls with beeswax mixed with pigment. Over time, it evolved into a revered art form used in funerary portraits in Egypt and murals in Rome. The word "encaustic" comes from the Greek enkaustikos, meaning "to burn in," reflecting the process of fusing wax with heat. This medium, rich in texture and permanence, preserves color and detail for centuries. Its revival in modern times speaks to its tactile depth—offering artists an alchemy of emotion, layering, and history embedded in every brushstroke.

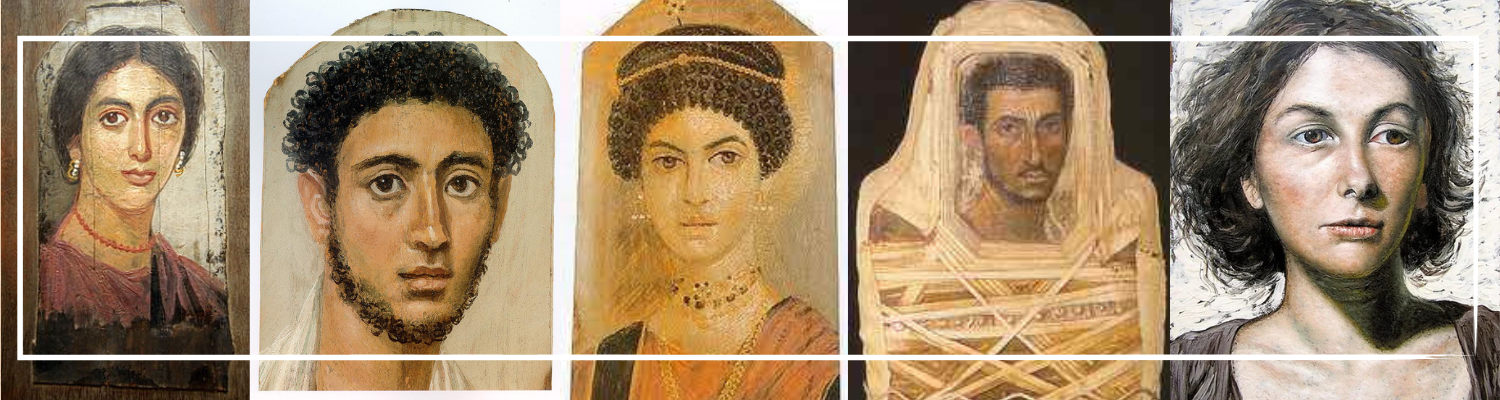

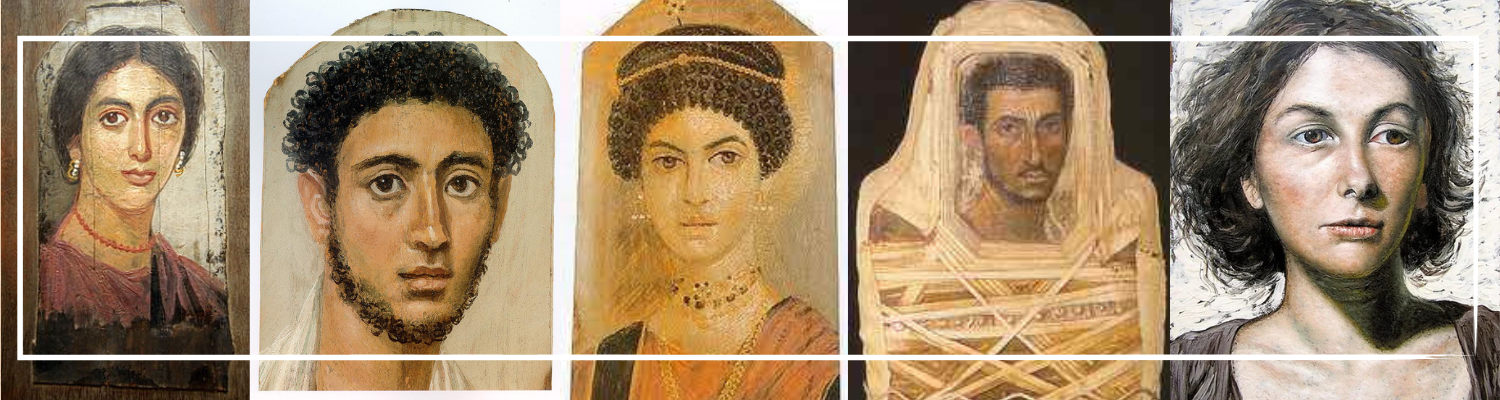

Encaustic painting traces its origins to ancient Greece, as early as the 5th century BCE. It wasn’t just an art form—it was a craft of preservation, of storytelling in wax. Greek mariners used it to waterproof and decorate their ships, eventually evolving the technique into something more expressive and revered. By the time of the Roman-Egyptian period, encaustic became immortalized in the Fayum mummy portraits—astonishing likenesses painted onto wooden panels placed over faces of the dead. These works, still vivid today, whisper across millennia, proving encaustic’s durability. There’s a reverence in this longevity, as if the very act of fusing wax with fire captured time. To know encaustic’s history is to feel its echo—a continuity of touch, technique, and spirit passed down not just through art, but through the enduring scent of beeswax and the flicker of flame that once lit an ancient artist’s studio.

Encaustic has passed through many hands—each leaving traces like fingerprints in wax. The ancient Greeks first developed the technique, using it to paint warships and statues, giving their marble gods a pulse of color. The Romans embraced it, most notably in the Fayum portraits of Egypt—where faces live on in softened wax. Later, the technique quieted, falling out of mainstream use during the Middle Ages due to its demanding nature. But it wasn’t forgotten. In the 20th century, artists like Jasper Johns revived encaustic for modern audiences. His Flag painting from 1954 used encaustic to layer meaning—personal, political, national—into the folds of painted wax. Today, contemporary artists continue the tradition, blending storytelling with substance. So, who used encaustic? Those who saw art not just as image but as atmosphere—those willing to wrestle with heat to reveal truth through texture.

When we trace the lineage of encaustic, our gaze often lands on the Fayum mummy portraits—ethereal, intimate, and astonishingly alive. Created in Egypt during the Roman period (roughly 1st to 3rd century AD), these paintings weren’t hung on walls but placed over the faces of mummified bodies. Eyes wide, expressions calm, they feel less like artifacts and more like people we almost remember. The most famous among them isn’t one singular portrait, but rather the collective aura they emit—a silent gallery of humanity preserved through wax and fire. These works stand as proof that encaustic isn’t merely decorative—it’s deeply connective. They transcend their funerary context and whisper across centuries, defying decay. What strikes us isn’t just technique, but truth—life held still, not deadened. These are not just relics; they are echoes, remarkably unblurred by time.

Encaustic painting, a richly layered and tactile art form, combines molten beeswax with natural pigments and damar resin. Artists apply this mixture to a rigid surface—often wood—using brushes or metal tools while the wax remains warm. Heat is essential: a heat gun or blowtorch fuses each layer, enhancing depth and luminosity. Carving tools, scrapers, and palette knives shape texture and reveal underlying hues. Mixed media—paper, fabric, or found objects—can be embedded into the wax, lending narrative layers. The result is a vibrant, durable surface with organic imperfections, echoing both control and spontaneity—a delicate balance between craftsmanship and emotional resonance.

The essential material in encaustic painting is a blend of natural beeswax and damar resin, infused with pigment. These components form the paint itself, which is applied hot and fused with heat. Beyond the wax, artists use a variety of tools: brushes that can withstand high temperatures, metal spatulas for scraping and sculpting, heat guns or blowtorches for fusing layers. The support surface must also be compatible—typically wood panels, as they offer stability and can endure repeated heating. But encaustic is generous in its inclusivity. Artists embed materials like fabric, paper, photographs, or even natural elements like feathers or leaves. Each inclusion becomes suspended in wax, preserved like an insect in amber. This material interplay creates a sense of time layered into matter. In encaustic, material isn’t just medium—it’s metaphor. Every chosen texture, every stroke of molten color, carries memory, weight, and a whispered dialogue between permanence and transformation.

The heart of encaustic painting beats within beeswax. It’s the preferred wax—pure, pliable, and naturally luminous. Beeswax offers a clean burn, a sweet scent, and a forgiving texture that responds well to pigment and manipulation. Its melting point hovers around 145°F (63°C), allowing it to be layered and reworked with gentle heat. Often, damar resin is added to increase hardness and stability, helping the final artwork better withstand time. Unlike paraffin or soy, beeswax is both archival and organic—it resists yellowing and holds pigment beautifully. The choice of wax isn’t just technical; it’s emotional. Beeswax connects us to something primal and ancient—hives, heat, honey, and home. It whispers of past rituals and natural order, and when used in encaustic, it turns each brushstroke into a quiet act of preservation. It's not just a medium—it's memory suspended in golden breath.

While both traditional gesso and encaustic gesso serve as primers, their chemistry and purpose differ subtly but significantly. Regular acrylic gesso is made for oil or acrylic paints; it creates a sealed, plastic-like surface that resists absorption. Encaustic, however, requires a porous surface to properly bond, which is where encaustic gesso enters—formulated with more absorbent ingredients like chalk, marble dust, and glue, it creates a matte, textured finish that allows molten wax to grip and fuse. The difference lies in their relationship to the medium: acrylic gesso protects the surface from soaking in too much, while encaustic gesso invites the wax in. Using the wrong one can cause delamination over time—encaustic paint may simply slide off a nonporous base. So, encaustic gesso isn’t just a preference—it’s a necessity for longevity and stability. It becomes the foundation where heat meets hold, and the artwork can breathe, expand, and endure.

In encaustic painting, the binder isn’t hidden or secondary—it’s central, physical, and aromatic. The binder is beeswax, often mixed with damar resin to harden the final surface and increase its durability. This combination is heated until molten, forming the very substance of the paint itself. Unlike oil or acrylic, where pigment is suspended in a medium that dries over time, encaustic fuses the pigment directly into the wax, creating a tactile surface that’s both durable and deeply dimensional. Beeswax doesn’t just hold pigment—it cradles it, giving it weight and form. When fused properly, the binder lends the artwork a skin-like finish: warm, semi-translucent, and almost breathing. It resists moisture, deters decay, and holds its brilliance for centuries. The binder in encaustic isn't just a technical necessity—it’s the soul of the medium, giving it voice, texture, and longevity. It binds not only particles, but also process, heat, and memory.

The best surface for encaustic painting is one that’s rigid, heat-tolerant, and absorbent. Wood panels—particularly birch plywood—are the gold standard, offering a stable foundation that won’t flex or warp under heat. Their natural porosity allows wax to anchor itself, creating a secure bond that withstands time. Unlike canvas, which can sag or buckle, wood holds firm, supporting the tactile layers encaustic requires. The surface is often primed with encaustic gesso to enhance adherence and texture. Some artists experiment with ceramic, metal, or thick handmade paper, but each comes with its own demands. The surface in encaustic painting is more than a backdrop—it’s a collaborator. Its texture affects how wax flows, how layers settle, how light travels through. Choosing the right one is not just technical—it’s emotional, intuitive. It’s where intention meets matter, where heat carves memory, and where the painting finds both its voice and its spine.

Working with encaustic is a tactile, meditative process—part painting, part sculpture. Begin by melting beeswax with damar resin, then layer it on a rigid surface using brushes or metal tools. Each stroke must be fused with heat—usually a torch or heat gun—to bind it to the layer beneath. The wax holds texture, light, and emotion, inviting both spontaneity and control. Pigments, photographs, or natural materials can be embedded, creating a dance between fragility and permanence. Let the surface speak—scrape, burnish, or carve to reveal hidden depths. Encaustic isn’t just a medium; it’s a dialogue with time, memory, and transformation.

Beginning encaustic painting is like preparing for a conversation in a new language—one spoken in heat, wax, and pigment. First, gather your core tools: encaustic medium (beeswax and damar resin), a heating surface like a griddle or hot plate, natural bristle brushes, and your pigments. Safety matters—ensure ventilation, because fumes, though minimal, can be harmful over time. Start by melting your medium slowly and evenly. Then, brush it onto your rigid surface (usually wood panels), layer by layer, fusing each with a heat gun or torch. Experiment. Let yourself play without seeking a final image. Carve, add texture, embed materials—this isn’t just painting, it’s sculptural storytelling. Encaustic isn’t about fast finishes; it’s about feeling your way through temperature and form. Be ready for unpredictability. Let the wax surprise you. Start small, observe how it cools, cracks, glosses. The technique grows with touch, with time, with reverence for its warmth.

Making encaustic paint is both alchemy and craftsmanship. Begin with beeswax—the golden base—and gently melt it over low, consistent heat. To that, add damar resin (crystallized tree sap) in a ratio of roughly 8 parts wax to 1 part resin. This blend, once fused, becomes your medium: durable, glossy, and archival. Next, introduce pigment—either dry powdered pigment or oil-free pastels—into the molten wax-resin mixture. Stir slowly, patiently, until the color blooms into the wax. Pour into molds or keep warm in tins for use. Each color requires its own pot, kept warm on a hot plate. As you apply it to your surface (usually a rigid one like wood), you’ll need to reheat and fuse each layer with a heat gun or blowtorch. The entire process demands presence—there are no shortcuts, only flow. It's not just mixing—it’s summoning an ancient language, molten and momentary.

Coloring encaustic wax is a subtle interplay between pigment and medium, between hue and heat. It’s not simply a matter of mixing in color, but of understanding how color behaves once bound in beeswax and resin. Pigments—dry powders or oil-based—are added directly into molten encaustic medium, which is typically a mix of beeswax and damar resin. There’s a kind of meditative rhythm to it: you heat, you stir, you wait for the blend to reach that quiet shimmer of readiness. Some artists prefer pre-made encaustic paints for consistency, but mixing your own allows a tactile relationship with your palette. The type of pigment affects opacity, translucency, and luminosity—earth tones whisper, synthetic hues shout. Each batch reflects the mood of its maker, its temperature, its timing. Color in encaustic is alive—it shifts with light, with layering, with every scrape and burnish. It’s not static; it breathes waxy, radiant stories.

Crayons can be used in a manner similar to encaustic painting, but they’re not a true substitute. While both share a wax base, crayons include additives—fillers, stabilizers, and less pigment—making them less pure, less responsive to the subtle layering encaustic demands. However, for experimentation or teaching, crayons offer a low-cost, accessible way to mimic encaustic’s tactile nature. When melted, they behave similarly, flowing into shapes and textures. But the surface they create is more brittle, less luminous, more prone to cracking. That said, the creative urge often finds its own language, and there’s something charming about using crayons to explore a tradition as old as encaustic. It becomes a bridge—between childhood materials and ancient technique, between spontaneity and permanence. So yes, you can use crayons, but the result won’t carry encaustic’s depth or archival quality. Still, the impulse to melt and mark is undeniably kindred.

Oil pastels can be used with encaustic, but with care and intention. They offer a velvety texture and rich pigment that contrasts beautifully against the smooth sheen of wax. Artists often draw or mark with oil pastels onto a cooled wax surface, then lightly fuse them with heat to meld them in. However, because oil pastels are made with non-drying oils and wax, overuse or excessive layering can lead to instability—smudging, blooming, or poor adhesion. The key lies in balance: using oil pastels as accents, subtle interventions rather than foundational elements. Their softness invites gesture, immediacy, a whisper of color against the more sculptural encaustic texture. When done thoughtfully, the result is layered, luminous, and full of movement. It becomes a conversation—between the opaque and the translucent, the solid and the smeared. Oil pastels don’t fight encaustic; they flirt with it, leaving behind traces of softness within the heat-forged whole.

Yes, you can draw on encaustic, and it’s a realm full of sensory potential. Once the wax surface has cooled and hardened, artists often scratch, etch, or incise into it, creating grooves to fill with oil sticks, pigment, or graphite. The surface itself becomes a palimpsest—layered, reworked, rewritten. There's something romantic and textural about dragging a charcoal stick or colored pencil across wax, watching it skip and resist, forcing you to adjust pressure and technique. The drawing becomes part of a larger narrative, weaving into the visual strata rather than sitting on top of it. And because encaustic is receptive to layering, the drawn marks can be encased in translucent wax—preserved, yet mutable. It’s not just about what’s added, but what’s revealed and concealed. Drawing here isn't just mark-making; it’s excavation, storytelling etched into a surface that remembers every scratch, every impulse.

Encaustic paintings possess a tactile, luminous quality—layered, molten beeswax fused with pigment gives them depth, texture, and a dreamlike translucency. Their surfaces are often rich, sculptural, and sensuous, inviting touch, with light refracting through built-up layers like frozen time. Brushstrokes, scratches, and embedded materials live within each tier, revealing stories in sedimented wax. Colors glow from within, not just on the surface, creating an aura of permanence and intimacy. The paintings breathe history and emotion—fragile yet eternal. Each piece carries a sense of memory, secrecy, and warmth, as if the past is sealed within its gleaming, whispering skin.

The encaustic look is tactile, luminous, and richly textured—less a surface than a skin with memory. It’s a visual warmth that feels almost biological, as though the painting breathes under its layers. Light doesn’t just bounce off; it sinks into translucent wax and glows from within, like amber catching fire. You might notice striations where the brush pulled wax into ripples, or subtle fissures and marks left by metal tools. There’s a weight to it, a depth, like something archaeological—art unearthed rather than painted. The surface can be polished to a high gloss or left matte and raw, depending on how much the artist wants to invite or withhold. Encaustic doesn’t settle for flatness. It resists smooth resolution. It catches shadows and reflects warmth. Its look is sculptural, sensory, quietly theatrical. It remembers every layer, every burnish, every mistake embraced as part of its final face.

Encaustic painting is special because it feels alive—alive in process, in texture, in time. Unlike other mediums that depend on drying, encaustic relies on the elemental power of heat. You paint with melted wax, fuse it with fire, and watch it solidify in moments. This alchemical dance of transformation—liquid to solid, fluid to fixed—is at the heart of its magic. The surface itself becomes a story: layers embedded, scraped back, painted again. Light doesn’t just reflect off encaustic; it moves through its translucent layers, creating a depth that feels almost geological. It's also archival, resisting moisture, decay, and fading. But perhaps what’s most special is the way encaustic invites intimacy. You sculpt with your hands, breathe with your torch, listen to the crackle and flow. Each piece is a tactile history—of choices, temperatures, impulses. Encaustic isn’t just painting—it’s an encounter with material, moment, and memory.

Bringing shine to an encaustic painting is not just about polishing—it’s about honoring its layers, its light, its skin. Once the surface cools and hardens, you begin with a soft, lint-free cloth. Gently rub in small circular motions, building friction—not too much heat, just enough to wake the wax’s natural luster. You’re not applying gloss; you’re revealing what’s already there. The more layers fused with care, the more radiant the finish. Some artists even use the heel of their palm to warm-polish—intimate, physical, like whispering secrets back into the surface. Time plays a role: encaustic gains depth as it ages, mellowing into an amber glow. You can also layer clear medium over colored areas to enhance luminosity, like sunlight trapped beneath skin. Shine isn’t about flash. It’s about resonance. In encaustic, the gleam feels earned—not sprayed on, but brought forth from within, one circular breath at a time.

Encaustic paintings, with their rich texture and vibrant layers, require careful attention to drying, durability, and storage. The wax-based medium demands patience as it dries quickly upon application but requires adequate time to fully set. Once dry, the painting’s durability depends on its composition, with proper sealing crucial to preserving its vibrant colors and intricate details. Storage should be in a cool, dry place to prevent melting or distortion. Avoid humidity and direct sunlight, which can damage the delicate balance of wax and pigment. Careful handling ensures the painting's longevity, maintaining its vivid and timeless essence.

Encaustic paint doesn't "dry" in the traditional sense—it cools and hardens. Because it's made of molten beeswax mixed with resin and pigment, its setting depends on temperature rather than time. Once applied, it solidifies quickly upon cooling, often within seconds. This immediate transformation creates a physical presence, a permanence that feels carved into time. But despite its fast solidification, it remains reworkable; reheating allows the artist to manipulate it again. This dual nature—firm yet flexible—makes encaustic feel almost like a dialogue rather than a monologue with the medium. Each stroke, once cooled, is a decision frozen, but not final. There’s a visceral tactility in watching wax transform from fluid to form, as if you’re not just painting but sculpting light and shadow. It’s this quality that makes encaustic both unpredictable and deeply intimate, turning the act of painting into a performance of temperature and intuition.

Yes, but not easily. Encaustic paintings can melt, but they won’t liquefy under typical indoor conditions. The melting point of encaustic medium—beeswax combined with damar resin—hovers around 160°F (71°C). That’s well above most home or gallery environments, but not impossible in direct sunlight or extreme heat, especially in poorly ventilated spaces. It’s more vulnerable to warping or softening than outright melting. You won’t wake up to a puddle, but you might notice subtle shifts if it’s hung in a sun-drenched room for months. Think of encaustic as you would a candle—not something you leave near a heater or in a hot car. Proper storage and display matter. But here’s the beauty: encaustic is also resilient. It doesn’t yellow, crack, or fade like other mediums. It’s been found in ancient ruins, still holding its glow. So yes, it can melt. But cared for, it endures like wax-bound memory.

Encaustic art, when preserved with care, can last centuries—timeless like a whispered memory etched in wax. The ancient Greeks painted with molten beeswax and pigment, and their works still breathe today from museum walls. Its resilience lies in its nature—waterproof, UV-resistant, and immune to yellowing. But its longevity depends on the artist’s hands and the environment’s mercy. Avoid extreme heat; cradle it away from direct sunlight. Encaustic doesn't crack under time—it deepens, evolves, almost like skin remembering touch. In the right conditions, it doesn’t just last—it lives, holding its colors like secrets waiting to be rediscovered.

Read More : Pichwai Traditional Wall Art for your Living Room Space

Encaustic painting, known for its vibrant, textured finish, offers unique advantages. The use of hot wax mixed with pigments creates a rich, glossy surface, ideal for layering and texture. Its durability is a significant benefit; encaustic works are resilient to light and environmental changes, unlike some other mediums. Additionally, its versatility allows for intricate details and complex patterns.

However, encaustic painting can be challenging due to its need for specialized equipment and the risk of overheating. The process is time-consuming, requiring precision and care, and the wax can be prone to cracking if not applied correctly.

Encaustic’s charm lies in its permanence cloaked in fluidity. Its luminous surface doesn’t just sit on a canvas—it breathes, reflects, absorbs. Once cooled, encaustic is durable—resistant to moisture, impervious to mold, and astonishingly archival. Unlike oil, it doesn’t yellow; unlike acrylic, it doesn’t crack under age. The layering process invites texture, embedding objects and emotion with equal ease. One can etch, carve, embed fabric or photograph—it’s a painter’s playground and a sculptor’s delight. Plus, it dries instantly upon cooling, offering immediate satisfaction without waiting days or weeks. There’s also a meditative quality to working with molten wax—a rhythmic heating, applying, fusing—that anchors the artist in ritual. And the finished piece? It holds a tactile memory, a depth of translucency that oil or watercolor can only hint at. Encaustic doesn’t just show an image—it lets the viewer enter it, layer by gentle layer.

Encaustic, though seductively rich and storied, carries its own quiet burdens. The process is labor-intensive—it demands constant heat, control, and care. One can’t simply dip a brush and begin; you must prepare, melt, and maintain a stable temperature or risk ruining the work. The tools required—heated palettes, torches, ventilation—form a ritualistic setting, but not always a forgiving one. It’s not travel-friendly or ideal for small studios with limited resources. Moreover, wax, though resistant to moisture, is vulnerable to high heat; a finished work exposed to direct sunlight or warm environments may soften or distort. There’s a delicate dance between creation and preservation, and not everyone is equipped for that responsibility. Mistakes can be difficult to undo once wax hardens, and layering beyond a point risks losing clarity. Encaustic is as much about restraint as expression, and therein lies its bittersweet, beautiful contradiction.

Encaustic painting isn’t difficult in the way that realism demands precision or watercolors demand restraint—it’s difficult in its demand for rhythm, patience, and a particular kind of trust. There’s a dialogue with heat and time that one must learn to respect. You don’t just paint—you melt, fuse, scrape, build, reheat, and coax form from fluidity. There’s always movement involved. It teaches you not to cling to perfection, because the surface can always shift. Mistakes? They become textures. Missteps? Layers. It can be frustrating, yes—tools must be warm, pigments must be stable, and every layer needs to be fused with care or it’ll crack or cloud. But there’s freedom too. You can start over, melt a mistake away. It asks you to be present, not precise; to let process lead. So, difficult? Yes. But only as any meditative act is—hard because it asks for your full self.

Fresco and encaustic may seem like distant cousins in the history of art, but they hold their own textures, temperaments, and philosophies. Fresco is a marriage of lime plaster and pigment—fluid, fast, irreversible. Applied on wet walls, it demands spontaneity wrapped in precision. Time is its master: the plaster dries, locks in color, and there’s no going back. Encaustic, on the other hand, is sculptural in spirit. It’s pigment melted into wax, painted hot, cooled fast. You don’t rush it; you build it, fuse it, scrape, layer, and smooth. Where fresco is about swift decisions etched in permanence, encaustic is about evolving surfaces and the memory of every touch. Fresco is architectural—it lives in stone. Encaustic is intimate—it lives in flesh-like wax. Both hold ancient lineages, yet speak in entirely different rhythms. One whispers from the walls; the other pulses from textured, luminous skins.

Impasto and encaustic both live in the realm of texture, but their materials and moods differ. Impasto is a painter’s bold gesture—thick paint (usually oil or acrylic) applied in expressive strokes, creating peaks and valleys. Think Van Gogh’s skies, where every brushstroke feels alive. It’s all about volume, presence, movement. Encaustic, by contrast, builds texture through heat and wax. You don’t just pile on; you melt, layer, and fuse. It’s more of a sculptor’s approach than a painter’s flourish. Impasto dries slowly, air-curing its heft over days or weeks. Encaustic cools quickly but asks for constant heat to manipulate. Impasto is drama; encaustic is intimacy. Both seduce the eye through light and relief, but one is a textured scream and the other a waxy whisper. Each holds emotion differently: impasto shouts what it feels; encaustic buries its stories, inviting viewers to dig through the sheen for meaning.

Encaustic and oil painting differ in texture, technique, and temperament. Encaustic uses heated beeswax mixed with pigment, applied in layers and fused with heat, offering a tactile, luminous depth—almost sculptural in feel. It dries instantly but requires precision and heat control. Oil painting, in contrast, thrives on patience—its slow drying time allows for blending, reworking, and emotional fluidity. Where encaustic feels elemental and visceral, oil is meditative and mutable. Encaustic speaks in textured whispers; oil in layered echoes. One burns into the surface; the other sinks into it. Both hold stories, but their voices are shaped by fire or time.

Encaustic and acrylic painting differ not just in medium but in soul. Encaustic uses heated beeswax mixed with pigment—each stroke sealed with fire, layered with history, evoking texture, memory, permanence. It breathes warmth, scent, and sculpture. Acrylic, water-based and fast-drying, offers control, clarity, and immediacy—a modern rhythm. It adapts, overlays, covers, reveals. Encaustic is ancient, tactile, luminous; acrylic is versatile, bold, and often unforgiving. One whispers through time, the other speaks in the moment. Both are voices—different in tone, in weight, in how they let the light in—but they carry the same ache: to preserve feeling in form.

Creating a safe and optimal studio setup for encaustic painting requires attention to both materials and environment. The workspace should be well-ventilated, free from dust, and have a stable temperature to ensure the wax doesn’t cool too quickly. For safety, it’s essential to use heat sources that are properly controlled, like a dedicated encaustic iron or griddle, to avoid accidental burns or fires. Additionally, proper storage of waxes and pigments in airtight containers minimizes the risk of inhalation. As for learning, starting with the fundamentals—such as layering and color manipulation—will give you a solid foundation for experimentation and growth in encaustic art.

Encaustic painting, while rich and textured, is generally safe when practiced with care. It involves heating beeswax mixed with pigments, so proper ventilation is crucial to avoid inhaling fumes. Use a temperature-controlled heat source—overheating wax can release harmful vapors. Always work in a well-ventilated space, preferably with a fume extractor or open windows. Avoid synthetic waxes or additives unless their safety is confirmed. Wear gloves when handling pigments and tools. Like any medium, it holds beauty and risk in balance; the process demands mindfulness—respecting both art and health. When treated with awareness, encaustic becomes a deeply expressive and safe craft.

Setting up an encaustic studio begins with embracing both art and fire. Choose a well-ventilated space, preferably with natural light. Invest in essentials: a heat gun, encaustic medium, metal palette, and natural bristle brushes. Use a sturdy worktable covered in foil or silicone. Store pigments and waxes safely, and maintain fire safety—keep a fire extinguisher nearby. Let the air carry the faint scent of beeswax. Organize tools intuitively—your hands should reach without thinking. Let silence settle before you paint. This isn’t just a studio; it’s a space where wax becomes memory, and heat unlocks what words cannot express.

Read More : Lepakshi Paintings : A Window into India's Mythological Past

Yes, encaustic can be applied to paper, but with a delicate hand and thoughtful preparation. The paper must be absorbent and sturdy—rice paper, watercolor paper, or even printmaking paper can hold the wax if supported properly. Because encaustic involves heat, thin paper can warp or buckle unless mounted onto a rigid surface. Yet, there’s something beautifully ephemeral about encaustic on paper. The wax soaks in, creating translucent veils of color that shift with light. It invites layering, embedding, and even sculpting directly onto the page. This fusion of fragility and permanence creates tension—the vulnerability of paper meeting the resilience of wax. It feels like painting on breath, like capturing something fleeting and making it stay. For artists seeking intimacy, immediacy, and texture, encaustic on paper offers a poetic canvas where each touch is absorbed, and each layer becomes a whisper frozen in time.